IMD gets August forecast wrong', 'Telangana: IMD gets it wrong on the second day too', 'Can we blame Met for getting storm 'wrong'?' – such are the headlines that have often dominated newsprint and online media when it comes to the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) and its weather predictions. An RK Laxman cartoon, published in a leading daily in 2007, depicts two people snug under their umbrellas, while the weatherman – the only one unaware about the approaching rains – completely drenched. An unofficial consensus seems to be that the weather department gets it wrong more often than not, and this leads to ignoring warnings that actually come to pass.

Both for the July 2005 Maharashtra floods and last year's August flood in Mumbai, there were warnings issued by the IMD, which were ignored by thousands of Mumbaikars, who braved the downpour to their own detriment.

So does the weather department really get it wrong? How accurate are the predictions anyway? And who, at the end of the day, should the layman follow when it comes to the forecasts? We asked the IMD and weather enthusiasts.

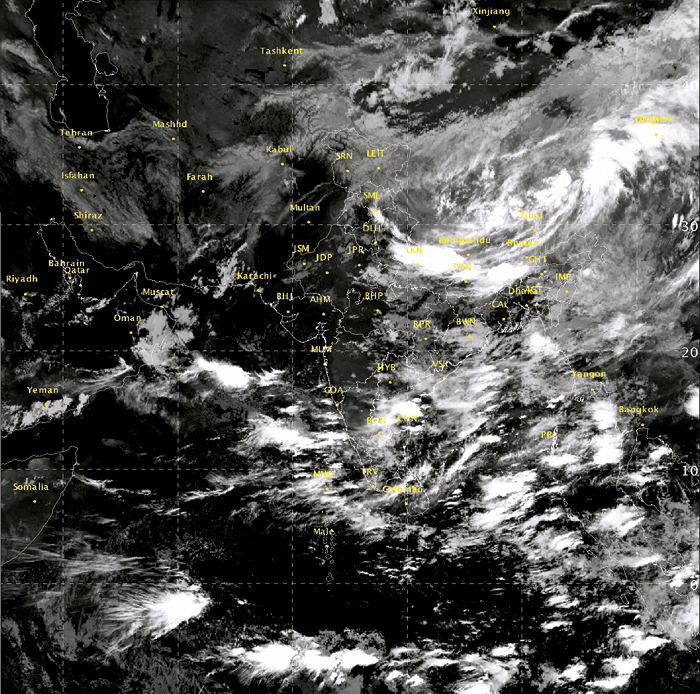

(INSAT image showing cloud formation over India in July 2018 from IMD archives)

Since RK Laxman's weatherman, technology has advanced vastly as far as both satellite inputs and surface weather stations are concerned. Automatic weather stations, radars, buoys, ships in the high seas as well as geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites provide the department with much-needed data, while the latest supercomputers and high-performance computers assimilate the vast information into concise reports and numeric codes. Swadesh Misra, an agro-meteorologist and erstwhile IMD officer in Kolkata, traces the history of IMD technology. "Satellites first came into the picture in the 60s, bringing weather reporting into the new age. They have, of course, been updated many times over the years, so that the current computer systems and satellites are up-to-date when compared to the rest of the world."

IMD was one of the first agencies to install supercomputers in the early 90s and later, brought in high-performance computing facilities for atmospheric research and weather forecasting. Two supercomputing facilities are available at Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune, and National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (NCMRWF) in Ghaziabad, with access made available all over the network. "We are currently working on further upgrading systems at Mumbai, Ahmedabad and Goa," says KS Hosalikar, deputy director general, IMD Mumbai. "I have been asked several times whether our technology is at par with those of more developed countries, and the fact is that we are. We exchange data on a global level with developed countries like the USA, UK and the likes, and we would not have been able to do so if we had subpar equipment or forecast percentage."

IMD data not only sent to global stations, and the United Nations weather department – World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), it is required in every walk of life closer home, be it agriculture, aviation, municipal and state governments, railways and individuals. Despite popular perceptions, a 2016 audit by WMO declared the IMD's forecasts as one of the best in the world, better even than countries like Japan. However, the capricious tropical weather keeps the department scrambling to give the right forecasts. "While there are a lot of other agencies now, I think that our range and scope is larger – we can reach out at the block and taluka level across the country," adds Hosalikar.

At the IMD centre in Colaba, barometers, thermometers in Stevenson screens, rain gauges and pan evaporation instruments are kept ship shape, function parallely with an automatic weather station, and are checked every three hours. Numeric codes and ever-changing satellite imagery are updated on dozens of computers, as forecasters try to predict weather patterns of the next 24 hours, up to 10 days and sometimes more.

Vagaries of the tropics

Vagaries of the tropicsOne major problem, however, remains the fact that India is located right in the middle of the tropics. The Tropic of Cancer slashes through it at 231/2 degree North, dividing the country into almost equal halves. While weather is more equitable in the sub-tropical or temperate zones, where a number of the developed nations are located, the unpredictable wind patterns in the tropics makes it difficult to give forecasts that are set in stone. India also receives 80 per cent of its rainfall in just four months from June to September. In winter, when most of the country is dry, the Tamil Nadu coast sees heavy rains. India's topography is a highly problematic one with two monsoons and higher intra-seasonal variability, as compared to other countries. These factors create challenges that are far greater than those faced by most developed countries.

"The entire Tibetan plateau also has a lot of bearing on the weather of India, and we have little to no data from there," says Misra. "Our surface stations are also less in number as compared to the USA, where they are placed very densely. Still, it's incorrect to say that IMD data goes wrong more often than not."

The problem, says Mumbai-based weather enthusiast Shantanu Patil – who uses satellite maps and other online data to do forecasts in Borivali – is not that the IMD gets the data wrong, but that it fails to update it on a real-time basis and convey it to the people. A mere gust of wind can blow away the clouds or a sudden dip in temperature may cause a cloudburst. If these changes are not updated on time, the reliability of the Met department becomes questionable. "It's as simple as tweeting or putting up constant updates on Facebook. The IMD needs to be more vocal," he says. "Hourly updates on the radio would also help. People are not aware of the IMD's correct predictions because they often do not reach them. The mistakes are always pointed out."

Hosalikar himself admits that a higher awareness about Met data is needed. "We have started to conduct awareness programmes. This year, we conducted over 25 workshops across the board, from the railways and the fisherman's unions to the BMC and schools," he explains, adding that schools have also started including more weather-related chapters in their syllabus.

Over the past year, weather enthusiasts such as Patil have started using data available in the public domain to put forth forecasts on the micro level. While Patil covers Borivali, Ankur Puranik, a ham radio operator and weather enthusiast operates from Wadala. "We owe most of our information to the IMD's satellite images, and some ham images that we also have access to," says Puranik, whose interest in weather stemmed from the forecasts they did as part of their radio activities.

He adds that amateur weathermen and the IMD have a symbiotic relationship – a give and take of information and expertise. "Mr Hosalikar is a part of our group on WhatsApp, and shares his views and satellite images, while we also share the data we get through our ham radio signals."

The deputy director general also welcomes these enthusiasts, who supplement the data, admitting that this exchange creates greater involvement of civilians in weather forecasts. Similar exchanges in the US actually help with detection of hurricanes, so the mushrooming amateur weather stations are a welcome step. But Hosalikar warns against overstepping the bounds of local broadcast. "If you are an enthusiast, you must know your limitations. You may have one set of observations. But there are over 1,000 images on our website. Proper standardised training is given to Met officials over a period of time. Sometimes, weather enthusiasts start claiming to be the authority to follow with little knowledge, and they talk loudly," he sighs.

Still, weather predictions on a micro-level are helpful to the local city-dwellers. "People in my society or in my acquaintance consult me about whether they should step out if it is raining," admits Puranik, adding that he makes it a point to put up a status on Facebook and WhatsApp each morning, getting up at 4.30am to ensure that he has the bulletin out in time. "I do this only during the monsoon as that's when we are needed the most. It's my way of helping out my country," he says, humbly.

Though these efforts are much appreciated, local weather enthusiasts have a limited bandwidth, reaching only a few 100 out of millions of civilians. The solution, says Patil, lies in an all-purpose mobile application that will help detect real-time data. While AccuWeather, Meteoblue, Weather and Clock and Windy are apps by private companies that he recommends, nothing would beat a similar application brought out by the IMD. "Such an app may leave us local forecasters with nothing to do, but it would be worth it," jokes Puranik.

An app of this nature is actually in the IMD pipelines. "We are coming up with a mobile application through which you can check the forecast in your area every 15 minutes. We are looking to launch this for the entire Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) area as it would be highly useful to the average Mumbaikar," he says. Hopefully similar applications for the rest of the country will follow.

The flip side to having an app that will reach people at the micro-level is to find a way to gather data from a denser network of surface stations. While currently, the IMD has automatic weather stations at a district level, the next step is to set them up at a block level. "We started district-level predictions 10 years ago but a denser observation network is needed at the block level, so that the models will give even better forecasts. This requires enormous investment in terms of installation as well as maintenance but this is the next step that we have in mind," he admits. "We must have a more integrated approach that reaches people at all levels."

MISS