While organisations are not very comfortable with the idea of having Bonds loose within, they are open to the idea of innovation-teams working far away

How out of box are you? Would you tolerate 007s in your organisation? Maverick management gurus keep raising these questions in their quest for an organisation which thrives on non-conformity. But what would it take to have a licensed demolition-man or an unlicensed innovator in your midst? Yes, what would it take to create a Bond who rejuvenates the company every time he breaks a rule?

One management guru says Bonds are born, not made. Another says the problem is CEO-related. A CEO has to wear two thinking caps, that of M (Bond’s boss) and Q (the gadget-maker in Bond movies). M is an unusual boss: he doesn’t compete with Bond to show who’s boss; he allows him his flamboyance while laying down the big, broad, rules; and he backs him to the hilt. Q is the magician who regales Bond with gadgetry although he is always upset with Bond’s demolition spree. In a way, Q is Bond’s biggest challenge: his innovations represent the future that Bond must constantly unravel.

Both M and Q are essential to creating a climate where Bonds can be bred, nourished, tempted, and challenged. A colleague reminds me that one of the best examples of the M-Bond combo was the P V Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh duo. A non-competing boss, Rao managed the administration, allowing Singh to launch the process of liberalisation. And, like M, Rao was able to create a hero by shielding him from the politics of the day and empowering him to fight the licence-raj. Rao even allowed Singh to be a Q as well.

How tolerant are organisations of mavericks? In The Living Company, a view of the company as a living being, author Arie De Geus gives a taste of tolerance. “Long-lived companies...generally avoided exercising any centralised control over attempts to diversify the company. Later, when I considered our research again, I realised that seventeenth-, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century managers would never have used the word decentralised; it was a twentieth-century invention. In what terms, then, would they have thought about their own company policies? As I studied histories, I kept returning to the idea of ‘tolerance’. These companies were particularly tolerant of activities in the margin; outliers, experiments and eccentricities within the boundaries of the cohesive firm, which kept stretching their understanding of possibilities.”

But the notion of tolerance has only gone so far as the creation of strait-jacketed Bonds or structured eccentricity. While organisations are not very comfortable with the idea of having Bonds loose within, they are open to the idea of innovation-teams working far away from the main organisation. One such team was the skunk works, a term still used by organisations when they work on secret, market-redefining, projects. According to Wikipedia, skunk works is the unofficial name for Lockheed Martin’s Lockheed Advanced Development Projects Unit and was the production unit responsible for a number of famous aircraft, including the U-2, the SR-71, and the F-117.

Samsung has its own skunk works in its VIP House, or Value Innovation Program. Fortune’s writer, Peter Lewis, descibes a recent VIP drill at the Korean consumer-electronics major: “These days team members are allowed to go home to sleep if they want to, although Samsung executives acknowledge—with obvious pride—that the building is occupied 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

In Leading the Revolution, Gary Hamel showcases the mavericks that changed their MI6es. “Inside IBM and out, (John) Patrick and (David) Grossman are today recognised for their pivotal contribution to IBM’s e-business metamorphosis...These two unlikely heroes—a software nerd and a corporate staffer—along with a pro-change CEO, helped give IBM the chance to do something it hadn’t for a couple of decades: lead from the front.”

The story of Sony’s James Bond is even more exciting. “Lacking any formal mandate, (Ken) Kutargi launched a bandit project that eventually led to the establishment of the Sony Computer Entertainment division in 1993 and the introduction of the PlayStation video game console the following year.”

But do Bonds arrive on the scene at the time of crises or can they be hired, trained, and then let loose? Perhaps the answer lies with the boss himself. Jim Collins defines the Level 5 leader as one who “blends extreme personal humility with intense professional will”. Such leaders can help to create a maverick counter-culture. For, only humility allows a boss to lead without actually leading. While a CEO’s intense professional will, like M’s, defines Bond’s broad focus, it gives Bond enough room to re-invigorate the organisation by attacking its stress-points: fossilised bureaucracy and age-old beliefs. Interestingly, both define current strategy.

The biggest problem, of course, is not about creating a nursery for baby Bonds. In fact, the real problem lies in the self-transformation of the CEO. After all, you need to be a Dr Yes to create a change-agent. And, yes, you can’t have a JB unless you have an M and a Q too.

![submenu-img]() Meet man, an Indian, whose family topped list of richest people in the UK with net worth of...

Meet man, an Indian, whose family topped list of richest people in the UK with net worth of...![submenu-img]() Pune: Tanker explodes in Pimpri Chinchwad, nearby hotels, houses and parked trucks damaged

Pune: Tanker explodes in Pimpri Chinchwad, nearby hotels, houses and parked trucks damaged![submenu-img]() Rohit Sharma lashes out at IPL TV broadcaster for 'breach of privacy'

Rohit Sharma lashes out at IPL TV broadcaster for 'breach of privacy'![submenu-img]() Heeramandi lyricist AM Turaz on Azadi: 'Women's contribution in Indian freedom movement has never been...' | Exclusive

Heeramandi lyricist AM Turaz on Azadi: 'Women's contribution in Indian freedom movement has never been...' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Kangana Ranaut reveals if she will quit films after winning Lok Sabha elections, calls Bollywood 'jhoothi duniya'

Kangana Ranaut reveals if she will quit films after winning Lok Sabha elections, calls Bollywood 'jhoothi duniya'![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer, daughter of milk vendor, who cracked UPSC in second attempt, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer, daughter of milk vendor, who cracked UPSC in second attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() UGC NET June 2024: Registration window closes today; check how to apply

UGC NET June 2024: Registration window closes today; check how to apply![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer, son of teacher from Rajasthan, who cracked UPSC after multiple failed attempts, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer, son of teacher from Rajasthan, who cracked UPSC after multiple failed attempts, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…

Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...

Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'

Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'![submenu-img]() Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024

Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera

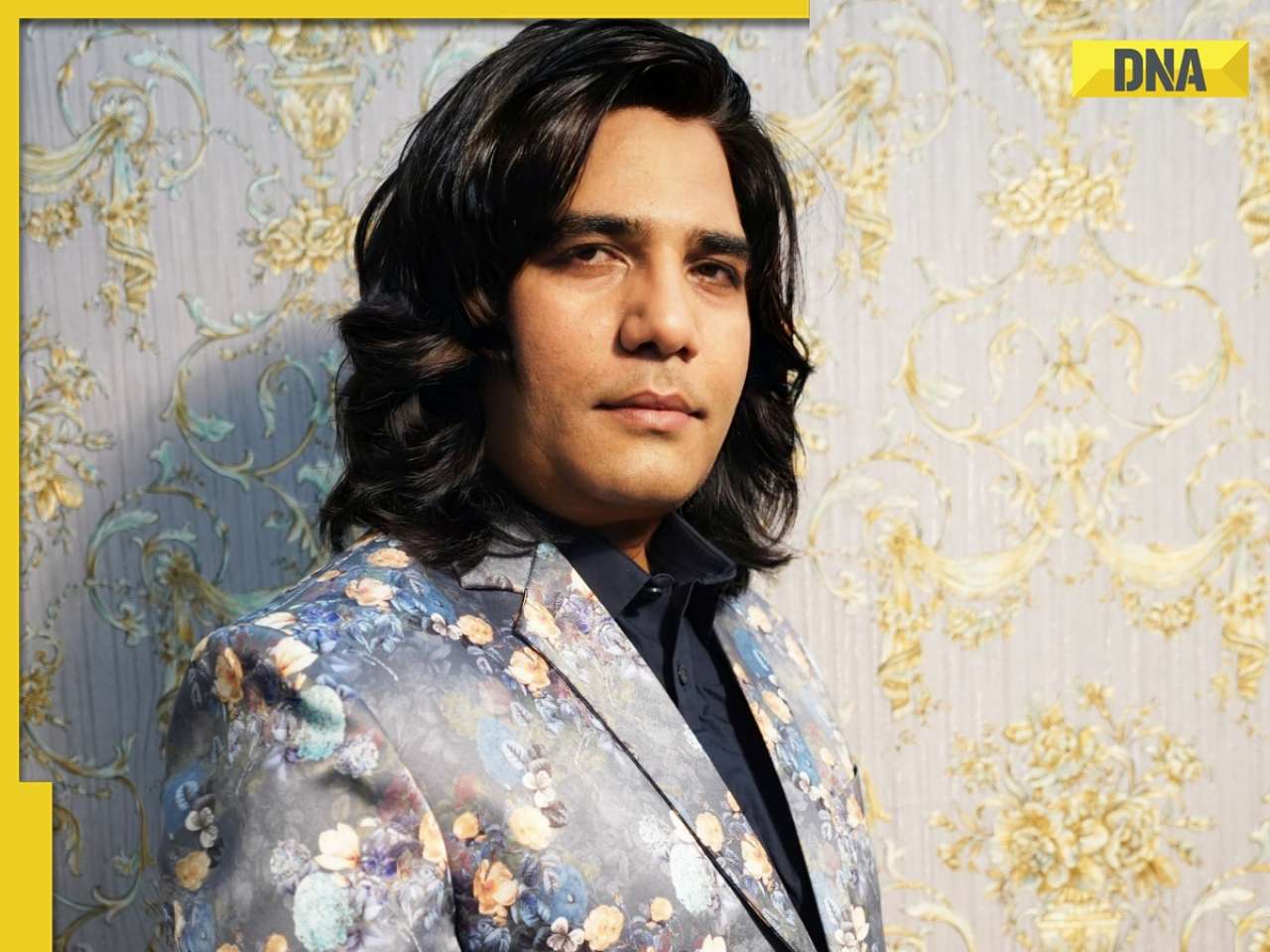

Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera![submenu-img]() Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’

Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Heeramandi lyricist AM Turaz on Azadi: 'Women's contribution in Indian freedom movement has never been...' | Exclusive

Heeramandi lyricist AM Turaz on Azadi: 'Women's contribution in Indian freedom movement has never been...' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Kangana Ranaut reveals if she will quit films after winning Lok Sabha elections, calls Bollywood 'jhoothi duniya'

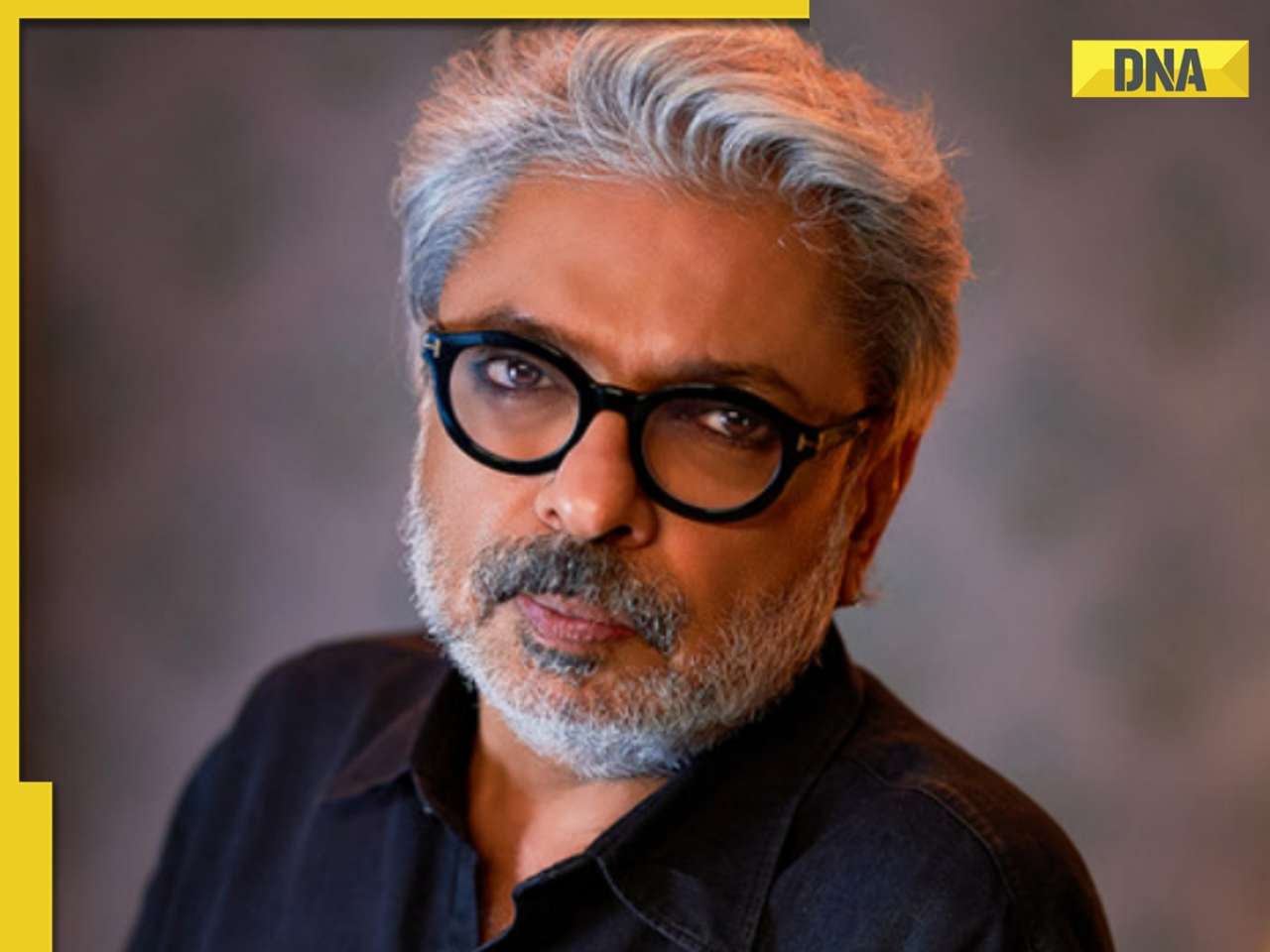

Kangana Ranaut reveals if she will quit films after winning Lok Sabha elections, calls Bollywood 'jhoothi duniya'![submenu-img]() Sanjay Leela Bhansali calls this actor his only friend in industry: 'He doesn't care about my film, he cares about me'

Sanjay Leela Bhansali calls this actor his only friend in industry: 'He doesn't care about my film, he cares about me'![submenu-img]() Jolly LLB 3: Akshay Kumar wraps up first schedule; local artiste reveals actor's inspiring daily habits

Jolly LLB 3: Akshay Kumar wraps up first schedule; local artiste reveals actor's inspiring daily habits![submenu-img]() Before Ranveer Singh, Deepika Padukone; Bajirao Mastani was announced with these two superstars in 70s, it got shelved

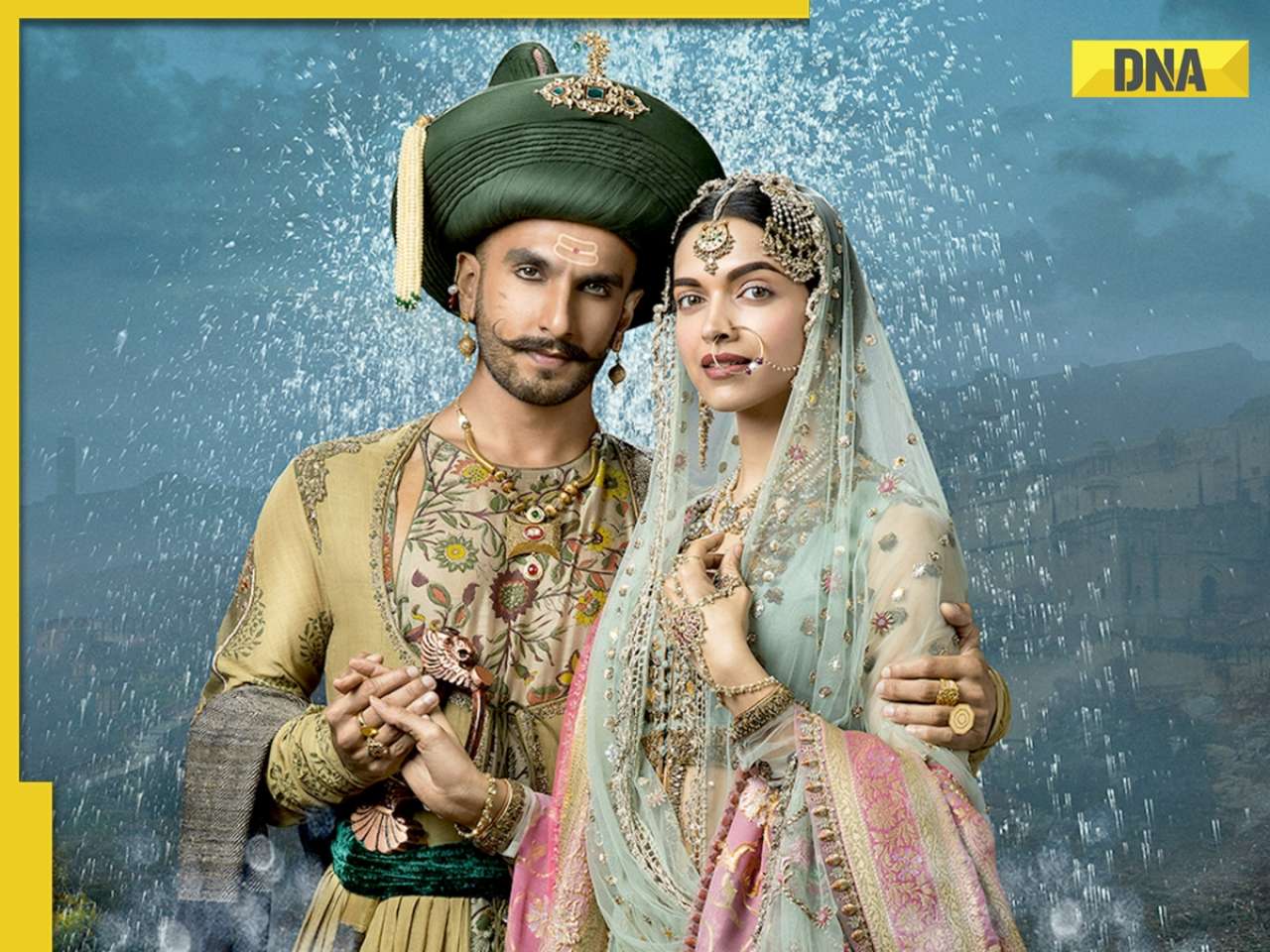

Before Ranveer Singh, Deepika Padukone; Bajirao Mastani was announced with these two superstars in 70s, it got shelved![submenu-img]() Viral video: Donkey stuns internet with unexpected victory over hyena, watch

Viral video: Donkey stuns internet with unexpected victory over hyena, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: 'Breathtaking' blue meteor illuminates skies over Spain and Portugal, watch

Viral video: 'Breathtaking' blue meteor illuminates skies over Spain and Portugal, watch![submenu-img]() Google CEO Sundar Pichai reveals his favourite foods in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru and they are...

Google CEO Sundar Pichai reveals his favourite foods in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru and they are...![submenu-img]() Cow fight injures two girls enjoying street snacks, video goes viral

Cow fight injures two girls enjoying street snacks, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man sets up makeshift hammock on bus, internet reacts

Viral video: Man sets up makeshift hammock on bus, internet reacts

)

)

)

)

)

)