There are many similarities between 25-year-old Ali Sethi and Zaki, the protagonist of his debut novel, The Wish Maker — both return to Lahore after college in the US.

There are many similarities between 25-year-old Ali Sethi and Zaki, the protagonist of his debut novel, The Wish Maker — both return to Lahore after college in the US, and they are both confronted with a city bustling with energy. Sethi’s novel spans three generations and paints a portrait of Pakistan that is as unique as it is familiar. In Mumbai to promote his book, Sethi took time out for a chat with DNA. Excerpts:

How did you get the idea for this novel?

When I joined college in the US in 2002, for the first time in my life, I was made conscious of where I came from and who I was. It was then that I decided to write a book set in Pakistan, which would tell the world what life in Pakistan is all about.

There’s been a lot of upheaval in Pakistan — not just recently. Has this affected you personally?

Public upheavals always impact people personally whether they are aware of it or not. My father has been arrested twice, once for publishing a pro-democracy book and the second time for making a speech in India in which he called Pakistan a “potentially failing state”. I was 15 then, the police broke into my house, beat up my parents, and jailed my father for a month. He suffered a heart attack in prison. He had been arrested for treason and sedition. One can be from a well-to-do-family and own a car but he or she still cannot be immune from the larger problems of the state. In Pakistan, anyone can be arrested for things like treason and blasphemy. It is so ridiculous. One person may testify against another, saying that he had heard him insulting the prophet. And that person can be sentenced to death, as blasphemy is punishable by death.

As a writer, what can you say about the situation in Pakistan at present?

Pakistan is in a very interesting state right now. In the sphere of education, we have always had two compulsory subjects called Islamiyat and Pakistan studies. These two subjects are not religious studies, they are distorted Islamic studies. Over the years, dictators have come and gone and each one has revised textbooks to suit their purposes. A whole generation has grown up on these books and over teachings of how women should not work and how they should always wear burqas and not show their faces. It has become difficult for these people to later reconcile themselves to the fact that what they grew up learning was false and distorted. And that is what is happening in Pakistan right now. People are suffering from an identity-crisis and raising questions about who is to blame for their state.

What about the role of the media there?

In the last five years, an independent media has for the first time surfaced in Pakistan. There are about 30 to 40 TV channels and 40 per cent of Pakistan now has cable TV. That means people who previously had access to just one state-controlled TV channel now have access to multiple versions of things. There may thus be a Koran TV whose content is clearly Wahabi-driven, where they say things like nail polish is not allowed. But there are also channels where women activists declare that the country should be secular and that women and men are equal. There is a new-found freedom where people are openly discussing politics and spouting words like ‘secular’, which was unheard of till a while back.

There are similarities between the protagonist and you. How autobiographical is the book?

I took three years to write this book. Had it been solely autobiographical, I would have finished it sooner. The novel is a mix of imagination, research and personal accounts.

You paint a wide canvas in the book, travelling from urban settings to rural ones, the 1990s to the Partition days, and use first person as well as third person narratives.

When I started writing, I realised that the landscape forming in front of me was mostly upper-middle-class, very urbane, and almost completely set in the 1990s. Then I decided I had to go to rural Punjab, to the life of Naseem, the maidservant, go back to the 1980s to write about what the protagonist’s mother Zakia went through, and then to the days of the Partition, to find out about the grandmother Daadi and the atmosphere in Pakistan then. I found that it would be impossible to write about present day Pakistan without referring to the past. I had to write about the 1980s, when the press was censored, when blank spots would appear in newspapers, when people grew up without information. Residents may live in a city called Lahore in a chowk called Lakshmi Chowk and near a place called Krishan Nagar, but they would not know that these places were once inhabited by people of another religion, people who were very different in their ways. The epigraph in my book is a quote by George Eliot which goes, “The difficult task of knowing another soul is not for young gentlemen whose consciousness is chiefly made up of their own wishes.” The novel is an attempt to exit oneself temporarily and understand how other people are experiencing the same world that you are living in. I could not confine myself to one story, or to one kind of experience. I had to travel further.

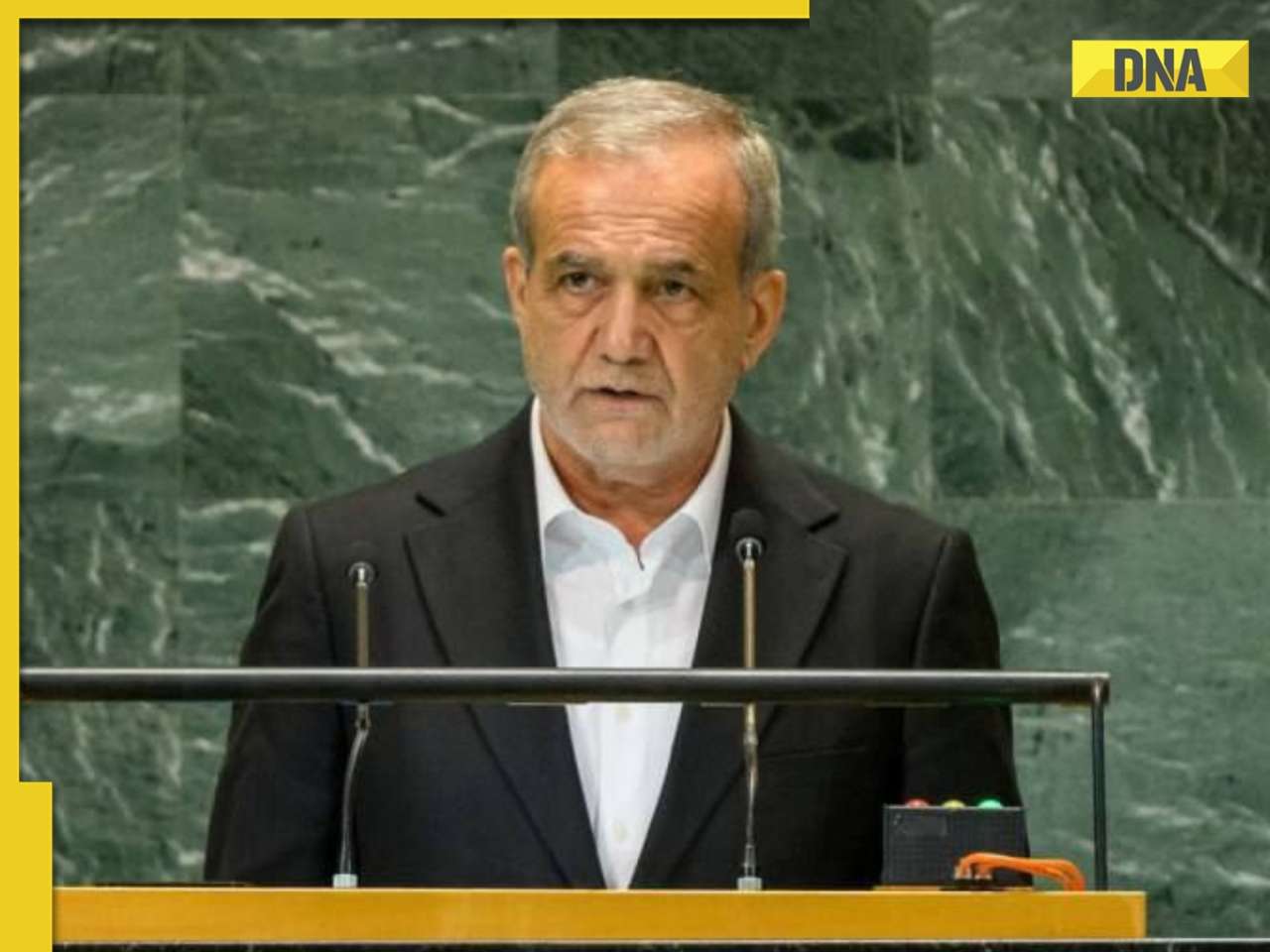

![submenu-img]() Iran launches dozens of ballistics missile at Israel, shelter-in-place order issued

Iran launches dozens of ballistics missile at Israel, shelter-in-place order issued![submenu-img]() Diplomatic Discord: Lebanon's Crisis and Iran's Strategic Posturing

Diplomatic Discord: Lebanon's Crisis and Iran's Strategic Posturing![submenu-img]() Watch: Shark Tank India season 4 starts filming with OG judges and new hosts, netizens ask premiere date

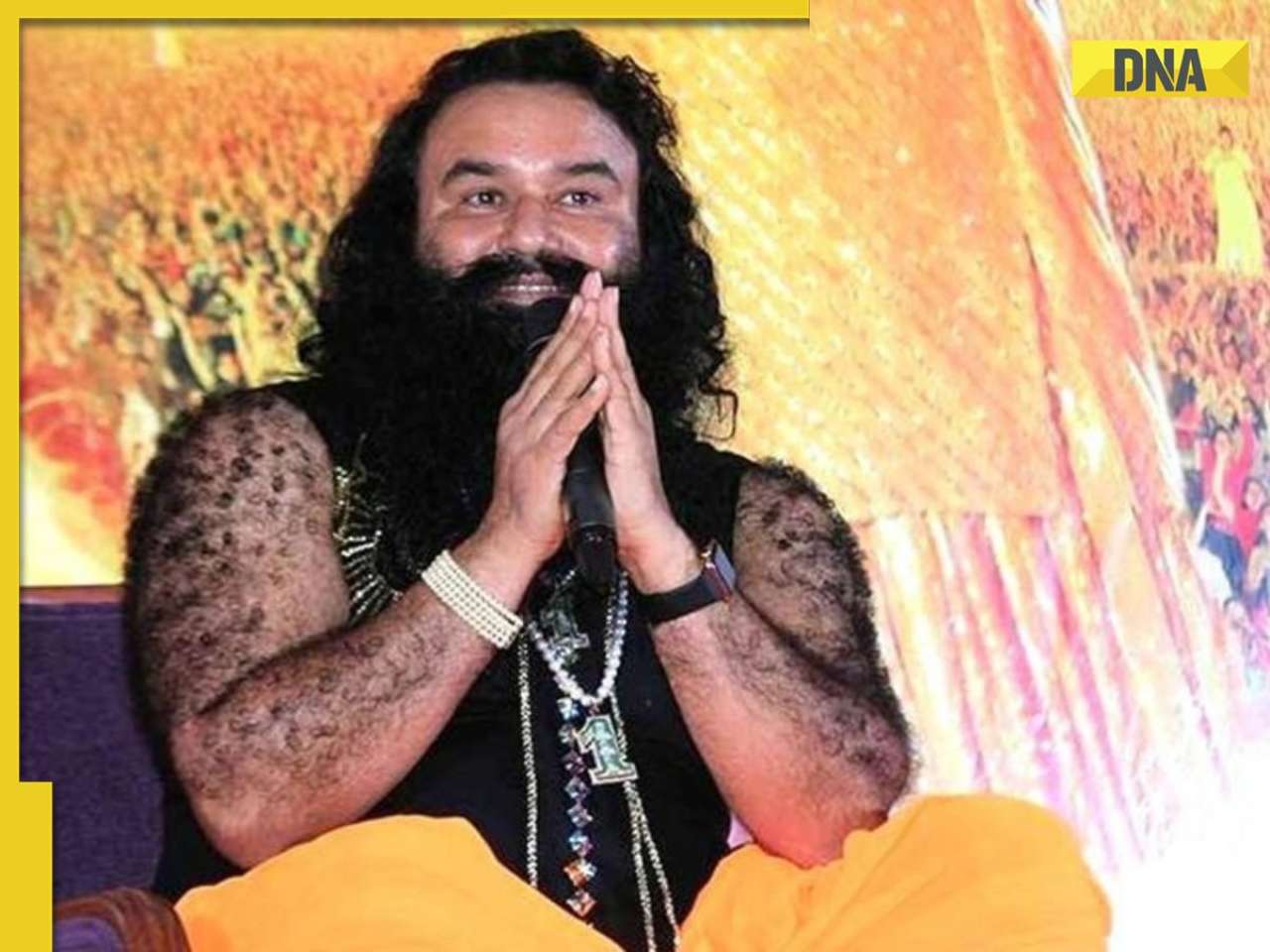

Watch: Shark Tank India season 4 starts filming with OG judges and new hosts, netizens ask premiere date![submenu-img]() Dera chief, rape convict Gurmeet Ram Rahim gets parole ahead of Haryana elections

Dera chief, rape convict Gurmeet Ram Rahim gets parole ahead of Haryana elections![submenu-img]() Top Nephrologists of the country: Redefining excellence in Renal Care

Top Nephrologists of the country: Redefining excellence in Renal Care![submenu-img]() Congress या BJP हरियाणा में 'ब्राह्मण' किसके लिए बनेंगे 'तुरुप के इक्के?'

Congress या BJP हरियाणा में 'ब्राह्मण' किसके लिए बनेंगे 'तुरुप के इक्के?'![submenu-img]() नोएडा में फर्जी कॉल सेंटर का भंडाफोड़, 15 लोग गिरफ्तार, विदेशी नागिरकों को ऐसे लगाते थे चूना

नोएडा में फर्जी कॉल सेंटर का भंडाफोड़, 15 लोग गिरफ्तार, विदेशी नागिरकों को ऐसे लगाते थे चूना ![submenu-img]() महिलाओं को मारना, काटना, टुकड़े करना Othello Syndrome या मर्दानगी की ताकत? पार्टनर पर बहुत गुस्सा आए तो क्या करें

महिलाओं को मारना, काटना, टुकड़े करना Othello Syndrome या मर्दानगी की ताकत? पार्टनर पर बहुत गुस्सा आए तो क्या करें![submenu-img]() Mandsaur Dalit Atrocity: मुंह काला किया, गले में जूते की माला डाली, दलित युवक की निकाली पब्लिक परेड, देखें Video

Mandsaur Dalit Atrocity: मुंह काला किया, गले में जूते की माला डाली, दलित युवक की निकाली पब्लिक परेड, देखें Video![submenu-img]() Mahindra Thar Roxx Bookings: नवरात्रि के इस दिन से शुरू हो जाएगी डिलीवरी, जानें इस दमदार SUV से जुड़ी सभी डिटेल्स

Mahindra Thar Roxx Bookings: नवरात्रि के इस दिन से शुरू हो जाएगी डिलीवरी, जानें इस दमदार SUV से जुड़ी सभी डिटेल्स![submenu-img]() BMW launches CE 02 electric scooter in India; price starts at Rs…

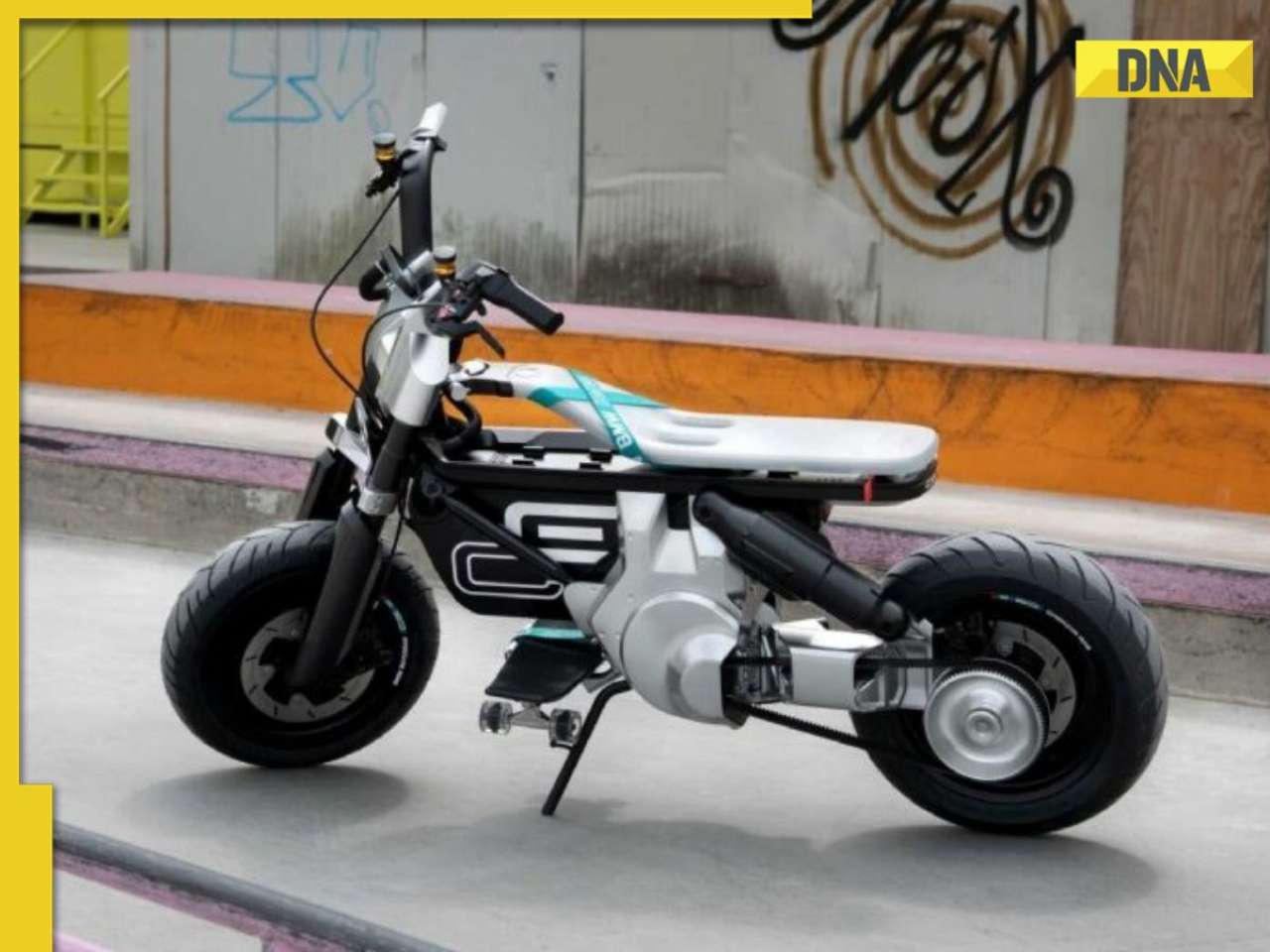

BMW launches CE 02 electric scooter in India; price starts at Rs…![submenu-img]() Mahindra Thar Roxx 4x4 prices revealed, starts at Rs…

Mahindra Thar Roxx 4x4 prices revealed, starts at Rs…![submenu-img]() Sebi gives nod to Hyundai India's Rs 20,000 crore IPO, listing month is...

Sebi gives nod to Hyundai India's Rs 20,000 crore IPO, listing month is...![submenu-img]() Tata launches Nexon iCNG, check price, mileage, other features

Tata launches Nexon iCNG, check price, mileage, other features![submenu-img]() This Indian car brand set to acquire 50% stake in Skoda Auto Volkswagen India, deal will cost Rs…

This Indian car brand set to acquire 50% stake in Skoda Auto Volkswagen India, deal will cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Meet woman, who is social media star, is married to IAS, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

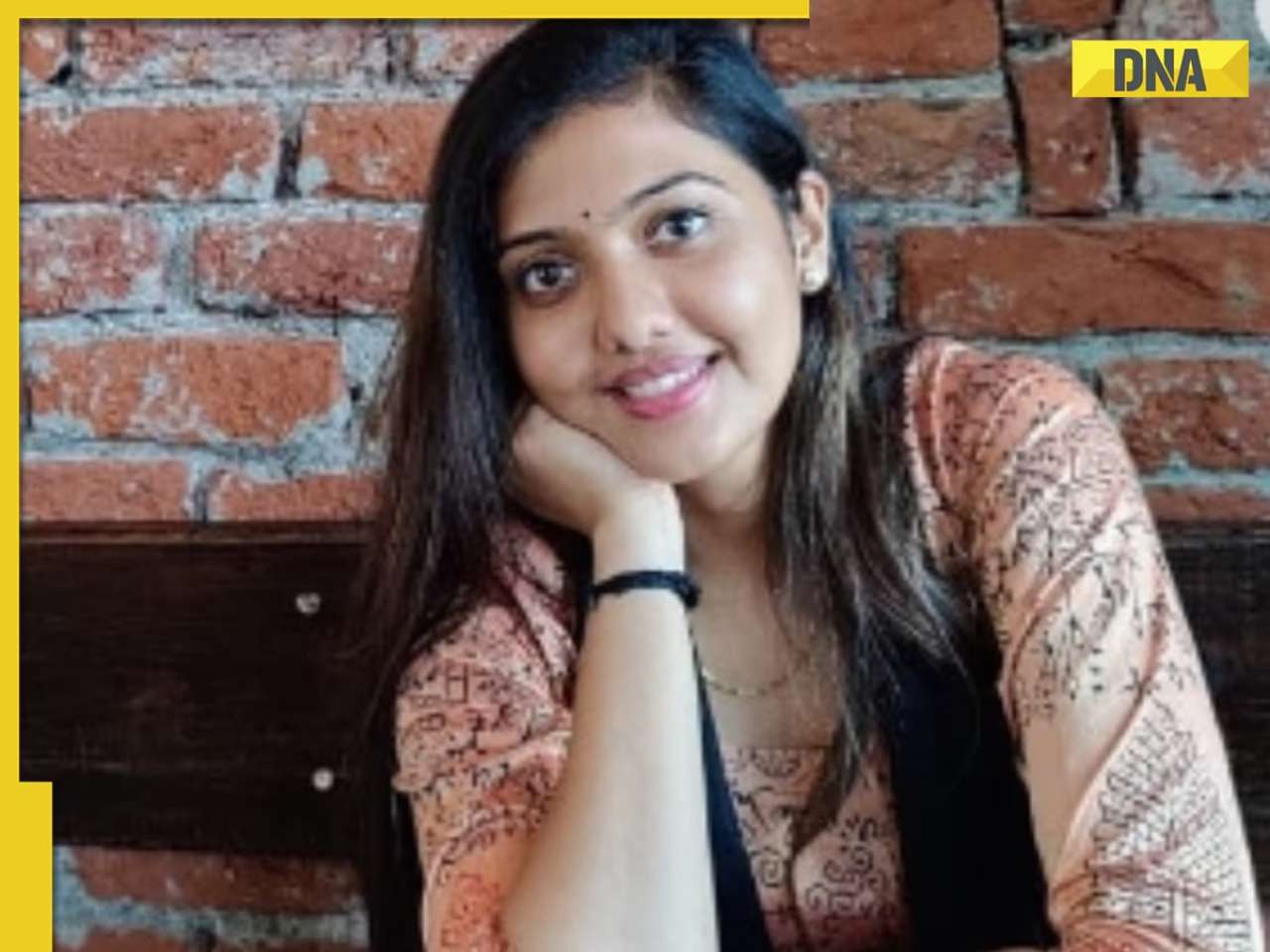

Meet woman, who is social media star, is married to IAS, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who cracked IIT-JEE with AIR 1, joined IIT Bombay, left after 2 years without graduation, he is now…

Meet Indian genius who cracked IIT-JEE with AIR 1, joined IIT Bombay, left after 2 years without graduation, he is now…![submenu-img]() Meet boy who started his company at 13, got inspiration from Mumbai's Dabbawalas, his business is...

Meet boy who started his company at 13, got inspiration from Mumbai's Dabbawalas, his business is...![submenu-img]() CAT 2024 application correction window closes today; check how to make changes, direct link here

CAT 2024 application correction window closes today; check how to make changes, direct link here![submenu-img]() Meet woman who left high-paying job at US govt agency for UPSC exam, became IAS officer with AIR...

Meet woman who left high-paying job at US govt agency for UPSC exam, became IAS officer with AIR...![submenu-img]() After Hassan Nasrallah's Death, This Cleric Is Now Tipped To Be Hezbollah Leader | Israel | Lebanon

After Hassan Nasrallah's Death, This Cleric Is Now Tipped To Be Hezbollah Leader | Israel | Lebanon![submenu-img]() Hashem Safieddine, Cousin Of Hassan Nasrallah To Become Hezbollah's New Chief | Israel-Lebanon War

Hashem Safieddine, Cousin Of Hassan Nasrallah To Become Hezbollah's New Chief | Israel-Lebanon War![submenu-img]() Israel Hezbollah War: Nasrallah's Death, A Turning Point for Hezbollah's Future? Experts Explain

Israel Hezbollah War: Nasrallah's Death, A Turning Point for Hezbollah's Future? Experts Explain![submenu-img]() Israel Hezbollah War: Hassan Nasrallah's Death Leads To Protests In J&K, Ex-CM Mehbooba Mufti Reacts

Israel Hezbollah War: Hassan Nasrallah's Death Leads To Protests In J&K, Ex-CM Mehbooba Mufti Reacts![submenu-img]() Israel Hezbollah War: Nasrallah's Death Leads To Protest By Women & Children In Jammu And Kashmir

Israel Hezbollah War: Nasrallah's Death Leads To Protest By Women & Children In Jammu And Kashmir![submenu-img]() Best Nutrition Software in India: Prim Transformed Dt. Renu Puri’s Business

Best Nutrition Software in India: Prim Transformed Dt. Renu Puri’s Business![submenu-img]() Sebi tightens F&O rules to curb speculative trading, to be effective from THIS date

Sebi tightens F&O rules to curb speculative trading, to be effective from THIS date![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's Reliance faces market turbulence as it loses Rs 80000 crore in just 48 hours

Mukesh Ambani's Reliance faces market turbulence as it loses Rs 80000 crore in just 48 hours![submenu-img]() BMW launches CE 02 electric scooter in India; price starts at Rs…

BMW launches CE 02 electric scooter in India; price starts at Rs…![submenu-img]() Anil Ambani ready to SHAKE UP market after board's approval to raise Rs 2,930 crore

Anil Ambani ready to SHAKE UP market after board's approval to raise Rs 2,930 crore![submenu-img]() Dera chief, rape convict Gurmeet Ram Rahim gets parole ahead of Haryana elections

Dera chief, rape convict Gurmeet Ram Rahim gets parole ahead of Haryana elections![submenu-img]() Manoj Gupta: Visionary Leader in IT Distribution

Manoj Gupta: Visionary Leader in IT Distribution![submenu-img]() Sadhguru’s Isha foundation raided by 150 police officers after father alleges daughters being held hostage

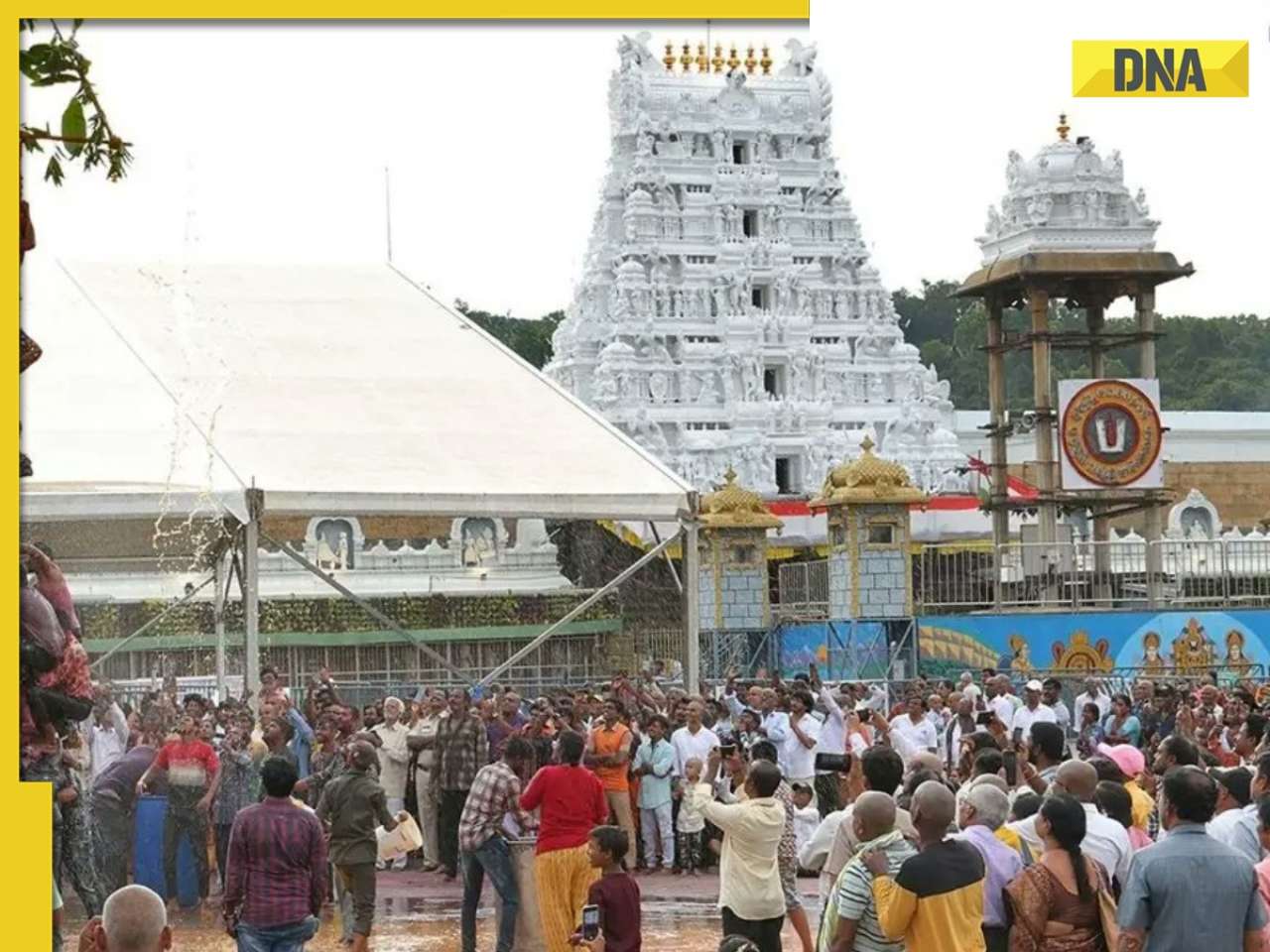

Sadhguru’s Isha foundation raided by 150 police officers after father alleges daughters being held hostage![submenu-img]() Tirupati laddu row: SIT probe into 'adulteration' temporarily stalled until SC hearing

Tirupati laddu row: SIT probe into 'adulteration' temporarily stalled until SC hearing![submenu-img]() Expert Insights from Rohit Reddy Chananagari Prabhakar on Advanced Data Management in Medical Education

Expert Insights from Rohit Reddy Chananagari Prabhakar on Advanced Data Management in Medical Education

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)