The renowned nine-metre tall marble Buddha at the Kyauk Daw Gyi pagoda in Mandalay, one of the largest in the nation, was carved in Sagyin.

For centuries, villagers at the foot of a hill in central Myanmar have carved a life out of stone.

"Sagyin" means marble in Burmese, and the village -- about 33km (20.5 miles) north of the regional capital of Mandalay -- is surrounded by a mountain range with large quantities of marble.

Two-thirds of its roughly 5,000 families survive on making statues, and the craftsmen for which the village is known are practically born with the skill, chiseling rock for as long as they can remember.

"If one doesn't have a degree, it is not easy to get a good job. I am not well-educated -- and I've been doing this job my whole life," U Pho Ni, 66, said.

U Pho Ni has been carving statues for four decades and has passed on the craft to his son, daughters and grandchildren. Chit Ko, his son, now runs the workshop, which specialises in 1 foot (0.348 metre) tall Buddha statues that are sold to Mandalay souvenir shops. His 19-year-old son, John Ko Ko, will inherit one day.

The whole family is involved. The men hammer and chisel the stone, while the women polish the finished statues. Men earn a daily wage of 2,000 kyat ($2.25), while women are paid 1,500 kyat ($1.70).

"This is our family's business. It's a legacy," John Ko Ko, himself a carver, said.

Unlike farmers, who are at the mercy of each harvest season's ups and downs, marble collectors and craftsmen say that as long as there is stone and demand for Buddha statues, their livelihood will remain profitable.

Sagyin marble is highly rated for its hardness and texture, varying from pure white to bluish gray in colour. But fine marble is becoming increasingly rare, and workers can toil for months to extract a 45-tonne slab that sells for up to $40,000.

Carving workshops began to thrive in the early 1990s, as production increased with the help of electric tools and the number of workshops tripled, said workshop owner U Maung Gyi.

The village is now home to more than 100 workshops, some of which export Buddha statues to China, Thailand, Singapore and Japan as well as some countries in Europe.

"That depends on the government. The businesses in this village would develop more if the government opened the market," U Maung Gyi said.

High transportation costs and the lack of good quality marble, which is controlled by the government, prevent the industry from expanding more robustly, U Maung Gyi said. Export products also carry a 10% tax.

In the city of Mandalay, where most of the products are distributed, workshops line Kyauk Sitt Thin, "Stone Carving Road."

The whir of chiseling tools reverberates across the powdery pavement, a key stop on sightseeing tours of the ancient royal capital.

Young apprentices, many of whom have quit school, work about eight hours a day in the workshops. They don't get paid in their first year of learning, but slowly start earning as their skill level increases.

Carving a life-sized statue can pay up to 5,000 kyat ($5.60) a day, a decent wage considering that the average monthly income in Myanmar is $50.

Carver U Taung Nyan, 60, has taken in countless apprentices in the past decades, and he is optimistic that the age-old craft will be kept alive.

"I'm really delighted when I see students I've taught making a good living as a craftsman," he said.

Burma's deep devotion to Theravada Buddhism also fuels the carving trade. Tens of thousands of temples across the country, as well as monasteries, public buildings and homes, contain a white-washed Buddha image.

The renowned nine-metre tall marble Buddha at the Kyauk Daw Gyi pagoda in Mandalay, one of the largest in the nation, was carved in Sagyin.

"If this mountain gets all used up, we will think of something else to do," said U Taung Nyan.

"I don't think the marble will run out, because this has been going on for generations. From past until present, the mountain continues to exist."

![submenu-img]() Priyanka Chopra kisses Nick Jonas as Malti Marie closes her eyes; see more family pics from singer's London concert

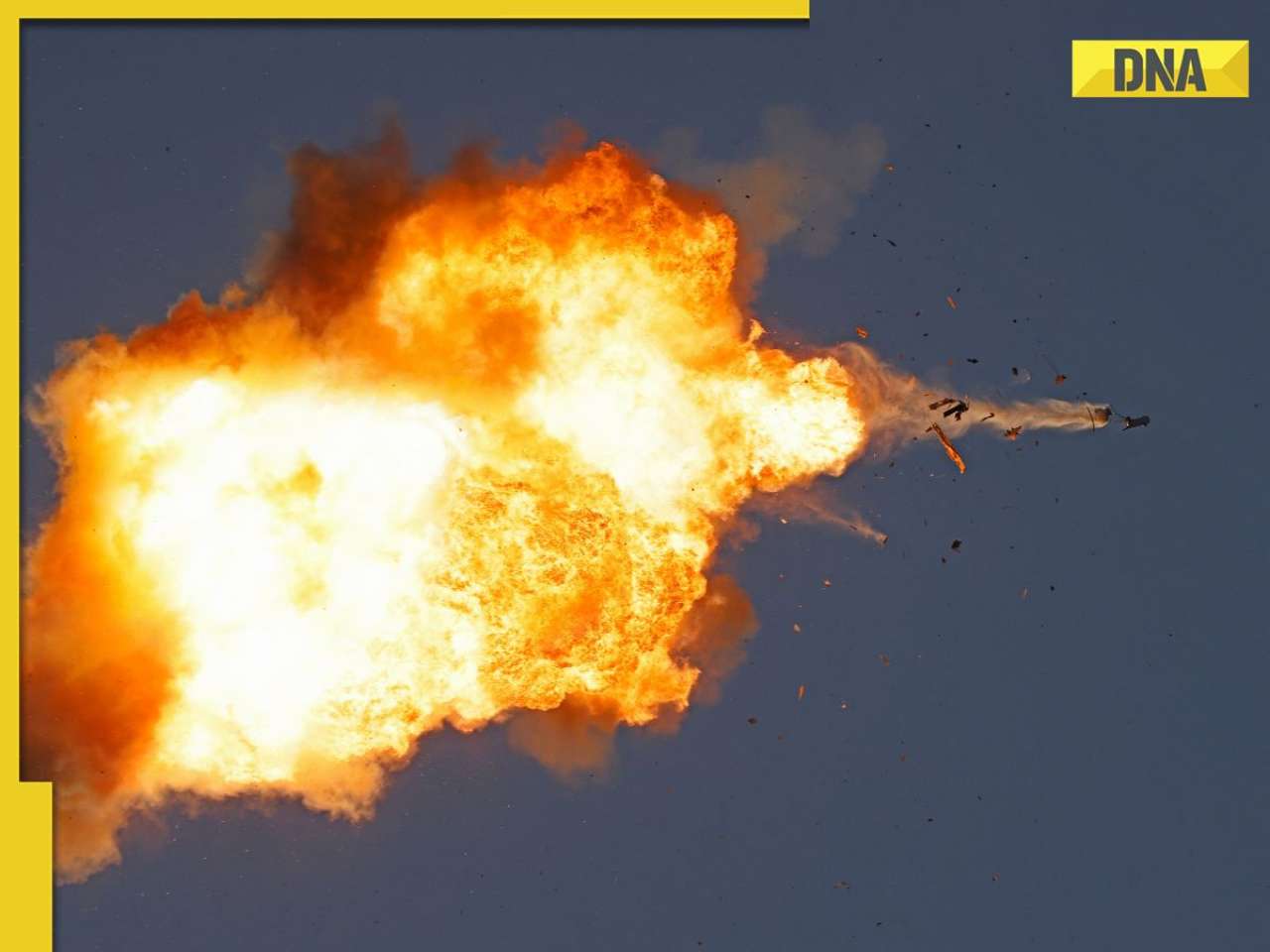

Priyanka Chopra kisses Nick Jonas as Malti Marie closes her eyes; see more family pics from singer's London concert![submenu-img]() Lebanon: Thousands of Hezbollah members wounded after communication devices explode mysteriously

Lebanon: Thousands of Hezbollah members wounded after communication devices explode mysteriously![submenu-img]() Meet woman, who is part of Rs 1257006 crore group, holds key position, she is Ratan Tata's...

Meet woman, who is part of Rs 1257006 crore group, holds key position, she is Ratan Tata's...![submenu-img]() Atishi's net worth: Know assets owned by Delhi's next CM

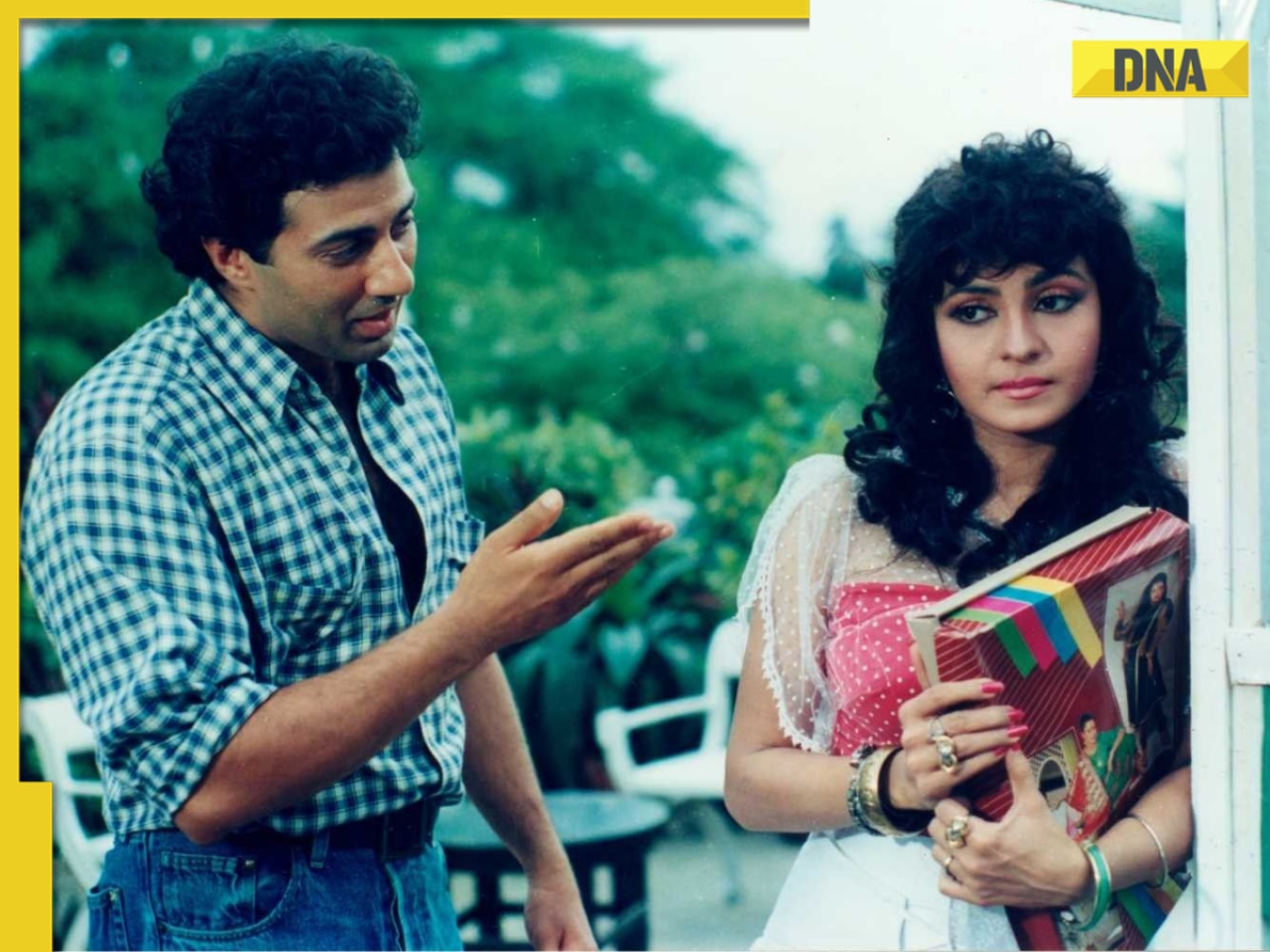

Atishi's net worth: Know assets owned by Delhi's next CM![submenu-img]() Meet Sunny Deol, Rajinikanth's heroine, in live-in relationship with married man for 35 years, refused to convert, now..

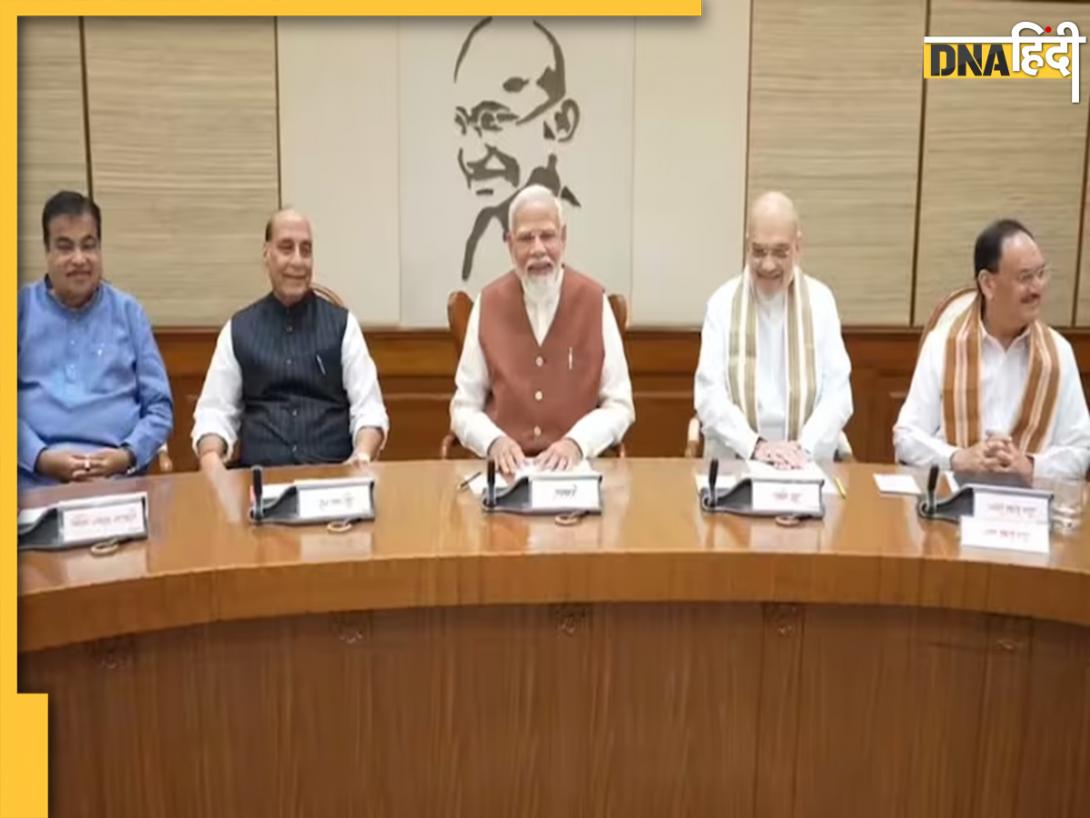

Meet Sunny Deol, Rajinikanth's heroine, in live-in relationship with married man for 35 years, refused to convert, now..![submenu-img]() One Nation One Election: मोदी सरकार का बड़ा फैसला, 'वन नेशन वन इलेक्शन' प्रस्ताव कैबिनेट से पास

One Nation One Election: मोदी सरकार का बड़ा फैसला, 'वन नेशन वन इलेक्शन' प्रस्ताव कैबिनेट से पास ![submenu-img]() सुनीता केजरीवाल को नहीं बनाया CM, आतिशी को मुख्यमंत्री बनाने के पीछे क्या है अरविंद केजरीवाल का 'मास्टरस्ट्रोक

सुनीता केजरीवाल को नहीं बनाया CM, आतिशी को मुख्यमंत्री बनाने के पीछे क्या है अरविंद केजरीवाल का 'मास्टरस्ट्रोक![submenu-img]() केंद्रीय मंत्री Ravneet Bittu के Rahul Gandhi को आतंकी कहने पर बवाल, कांग्रेस का जोरदार प्रदर्शन

केंद्रीय मंत्री Ravneet Bittu के Rahul Gandhi को आतंकी कहने पर बवाल, कांग्रेस का जोरदार प्रदर्शन![submenu-img]() सावधान! दुनिया के 27 देशों तक फैला Corona का नया XEC वेरिएंट, जानें क्या हैं इसके लक्षण

सावधान! दुनिया के 27 देशों तक फैला Corona का नया XEC वेरिएंट, जानें क्या हैं इसके लक्षण![submenu-img]() Priyanka Chopra ने सरेआम पति Nick संग किया ऐसा काम, देख बेटी Malti ने बंद कर ली अपनी आंख

Priyanka Chopra ने सरेआम पति Nick संग किया ऐसा काम, देख बेटी Malti ने बंद कर ली अपनी आंख![submenu-img]() Ford to return to India after 2 years with reopening of....

Ford to return to India after 2 years with reopening of....![submenu-img]() Maruti Suzuki launches new Swift CNG, check price, mileage, other features

Maruti Suzuki launches new Swift CNG, check price, mileage, other features![submenu-img]() ‘30 LPA, 3BHK, no in-laws’: Woman earning Rs 1.32 lakh salary lists demands for future husband, netizens say...

‘30 LPA, 3BHK, no in-laws’: Woman earning Rs 1.32 lakh salary lists demands for future husband, netizens say...![submenu-img]() In a big EV push, Centre launches Rs 10900 crore PM E-Drive scheme to replace…

In a big EV push, Centre launches Rs 10900 crore PM E-Drive scheme to replace…![submenu-img]() World’s longest car has helipad, swimming pool, mini-golf course, can seat over…; it cost…

World’s longest car has helipad, swimming pool, mini-golf course, can seat over…; it cost…![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, who controlled 25% of world's GDP, had 50 Rolls-Royce, way richer than Mukesh Ambani

Meet India's first billionaire, who controlled 25% of world's GDP, had 50 Rolls-Royce, way richer than Mukesh Ambani![submenu-img]() IAS vs IPS: Who earns more? Differences in power, role, responsibilities

IAS vs IPS: Who earns more? Differences in power, role, responsibilities![submenu-img]() Meet boy who got record-breaking salary package from Google, was former Amazon employee, not from IIT, IIM…

Meet boy who got record-breaking salary package from Google, was former Amazon employee, not from IIT, IIM…![submenu-img]() Meet man who became IPS, then cracked UPSC to become IAS officer with AIR 52, is now DM of...

Meet man who became IPS, then cracked UPSC to become IAS officer with AIR 52, is now DM of...![submenu-img]() Meet PHD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary but was fired within a year, he is now...

Meet PHD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary but was fired within a year, he is now...![submenu-img]() Kolkata Doctor Case: Protesting Doctors React After CBI Arrests Sandip Ghosh And Abhijit Mondal

Kolkata Doctor Case: Protesting Doctors React After CBI Arrests Sandip Ghosh And Abhijit Mondal![submenu-img]() Nitin Gadkari: Union Minister Nitin Gadkari Reveals He Was Offered Support For PM Post But Declined

Nitin Gadkari: Union Minister Nitin Gadkari Reveals He Was Offered Support For PM Post But Declined![submenu-img]() Kolkata Doctor Case: Junior Doctors Protest For 5th Night As Talks With CM Mamata Fail Again

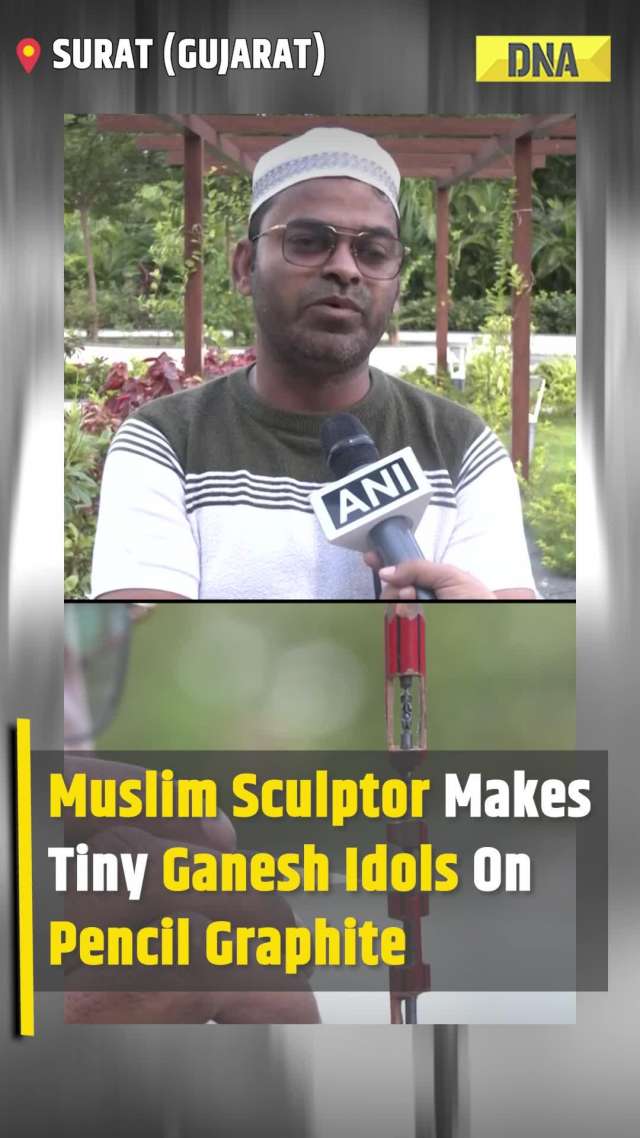

Kolkata Doctor Case: Junior Doctors Protest For 5th Night As Talks With CM Mamata Fail Again![submenu-img]() Muslim Sculptor Crafts Tiny Ganesh Idols On Pencil Graphite #shorts #viralvideo #ganesh

Muslim Sculptor Crafts Tiny Ganesh Idols On Pencil Graphite #shorts #viralvideo #ganesh![submenu-img]() Jaishankar: EAM Dr. S. Jaishankar On India-China Relations & Disengagement Problems | Ladakh

Jaishankar: EAM Dr. S. Jaishankar On India-China Relations & Disengagement Problems | Ladakh![submenu-img]() Meet woman, who is part of Rs 1257006 crore group, holds key position, she is Ratan Tata's...

Meet woman, who is part of Rs 1257006 crore group, holds key position, she is Ratan Tata's...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who lives in 2BHK flat in Mumbai, doesn't use any mobile, he is Ratan Tata's...

Meet man, who lives in 2BHK flat in Mumbai, doesn't use any mobile, he is Ratan Tata's...![submenu-img]() Amazon ends work from home, asks employees to return to office from...

Amazon ends work from home, asks employees to return to office from...![submenu-img]() Days after iPhone 16 series launch, Apple loses Rs 970000 crore due to...

Days after iPhone 16 series launch, Apple loses Rs 970000 crore due to...![submenu-img]() Meet man, BITS Pilani alumnus with over Rs 19500 crore net worth, now engaged in feud with brother over...

Meet man, BITS Pilani alumnus with over Rs 19500 crore net worth, now engaged in feud with brother over...![submenu-img]() This film was made in Rs 80 crore, actress scolded star kid while filming intimate scene; movie flopped, earned just...

This film was made in Rs 80 crore, actress scolded star kid while filming intimate scene; movie flopped, earned just...![submenu-img]() India’s richest child actor has net worth of Rs 8 crore, owns Rs 40-lakh luxury car, but nobody knows her 'real age'

India’s richest child actor has net worth of Rs 8 crore, owns Rs 40-lakh luxury car, but nobody knows her 'real age'![submenu-img]() 32-year-old superstar forcibly kissed 15-year-old co-star; left her traumatised, crying; later laughed about it saying..

32-year-old superstar forcibly kissed 15-year-old co-star; left her traumatised, crying; later laughed about it saying..![submenu-img]() Atishi is new Delhi CM: Know who was Delhi's first woman CM

Atishi is new Delhi CM: Know who was Delhi's first woman CM![submenu-img]() This actor worked in over 300 films, was abandoned by family, had no friends; was found with bottle of alcohol at...

This actor worked in over 300 films, was abandoned by family, had no friends; was found with bottle of alcohol at...![submenu-img]() Atishi's net worth: Know assets owned by Delhi's next CM

Atishi's net worth: Know assets owned by Delhi's next CM![submenu-img]() Thane Biggest Builders RK Builders and DHL Group Join Forces for Maharashtra’s Largest BTS Warehouse

Thane Biggest Builders RK Builders and DHL Group Join Forces for Maharashtra’s Largest BTS Warehouse![submenu-img]() Atishi to become Delhi CM: Know why she dropped her second name ‘Marlena’

Atishi to become Delhi CM: Know why she dropped her second name ‘Marlena’![submenu-img]() Arvind Kejriwal resigns as Delhi Chief Minister, tenders his resignation to LG

Arvind Kejriwal resigns as Delhi Chief Minister, tenders his resignation to LG![submenu-img]() Who is IPS Manoj Kumar Verma, the new Kolkata Police Commissioner?

Who is IPS Manoj Kumar Verma, the new Kolkata Police Commissioner?

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)