Early Earth was covered with oceanic crust-like surfaces.

Scientists have precisely dated the world's oldest rock at 4.02 billion years old, which suggests that early Earth was largely covered with an oceanic crust-like surface.

"It gives us important information about how the early continents formed," said lead author Jesse Reimink, a post-doctoral fellow at the Carnegie Institute for Science in the US.

"Because it's so far back in time, we have to grasp at every piece of evidence we can. We have very few data points with which to evaluate what was happening on Earth at this time," said Reimink.

Only three locations worldwide exist with rocks or minerals older than 4 billion years old: one from Northern Quebec, mineral grains from Western Australia, and the rock formation from Canada's Northwest Territories examined in this study.

While it is well known that the oldest rocks formed prior to 4 billion years ago, the unique twist on Reimink's rock is the presence of well-preserved grains of the mineral zircon, leaving no doubt about the date it formed.

The sample in question was found during fieldwork by Reimink's Ph.D. supervisor, Tom Chacko, in an area roughly 300 kilometres north of Yellowknife in Canada.

"Rocks and zircon together give us much more information than either on their own. Zircon retains its chemical signature and records age information that doesn't get reset by later geological events, while the rock itself records chemical information that the zircon grains don't," said Reimink, who completed his Ph.D. at the University of Alberta in Canada.

He noted that the chemistry of the rock itself looks like rocks that are forming today in modern Iceland, which is transitional between oceanic and continental crust.

In fact, Iceland has been hypothesised as an analog for how continental crusts started to form.

"We examined the rock itself to analyse those chemical signatures to explore the way that the magma intrudes into the surrounding rock," Reimink said.Reimink said.

One signature, in particular, recorded the assimilation step of magma from Earth's crust, researchers said.

"While the magma cooled, it simultaneously heated up and melted the rock around it, and we have evidence for that," Reimink said.

The research appears in the journal Nature Geoscience.

![submenu-img]() Tumbbad re-release trailer: Soham Shah returns to narrate horrors of Hastar, says 'jo tab nahi hua, woh ab hoga'

Tumbbad re-release trailer: Soham Shah returns to narrate horrors of Hastar, says 'jo tab nahi hua, woh ab hoga'![submenu-img]() IC 814 hijack survivor reacts to Netflix show controversy, says hijacker played antakshari with hostages, called her...

IC 814 hijack survivor reacts to Netflix show controversy, says hijacker played antakshari with hostages, called her...![submenu-img]() This actor is highest taxpayer of India, pays tax worth Rs 92 crore; not Amitabh, Akshay, Salman, Vijay, Prabhas

This actor is highest taxpayer of India, pays tax worth Rs 92 crore; not Amitabh, Akshay, Salman, Vijay, Prabhas![submenu-img]() 'IPL mein Rs 130 ka bhi nahi bikega...': YouTubers roast this Pakistani cricketer after disappointing Pak vs Ban series

'IPL mein Rs 130 ka bhi nahi bikega...': YouTubers roast this Pakistani cricketer after disappointing Pak vs Ban series![submenu-img]() Mahesh Bhatt to present adaptation of Fawad Khan-Mahira Khan’s Pakistani show Humsafar, aims to 'bridge' Indo-Pak divide

Mahesh Bhatt to present adaptation of Fawad Khan-Mahira Khan’s Pakistani show Humsafar, aims to 'bridge' Indo-Pak divide![submenu-img]() J-K चुनाव: BJP ने जारी की स्टार प्रचारकों की लिस्ट, PM मोदी समेत 40 नेताओं का नाम

J-K चुनाव: BJP ने जारी की स्टार प्रचारकों की लिस्ट, PM मोदी समेत 40 नेताओं का नाम![submenu-img]() मंत्री, विधायक... 24 घंटे में 22 नेताओं का इस्तीफा, हरियाणा में पहली लिस्ट आत�े ही BJP में भगदड़

मंत्री, विधायक... 24 घंटे में 22 नेताओं का इस्तीफा, हरियाणा में पहली लिस्ट आत�े ही BJP में भगदड़![submenu-img]() सीपीएम नेता सीताराम येचुरी की हालत गंभीर, दिल्ली के AIIMS में वेंटिलेटर पर किए गए शिफ्ट

सीपीएम नेता सीताराम येचुरी की हालत गंभीर, दिल्ली के AIIMS में वेंटिलेटर पर किए गए शिफ्ट![submenu-img]() 'PM मोदी किस बात पर मांग रहे माफी, भ्रष्टाचार या RSS...' शिवाजी स्टेच्यू विवाद पर बोले राहुल गांधी

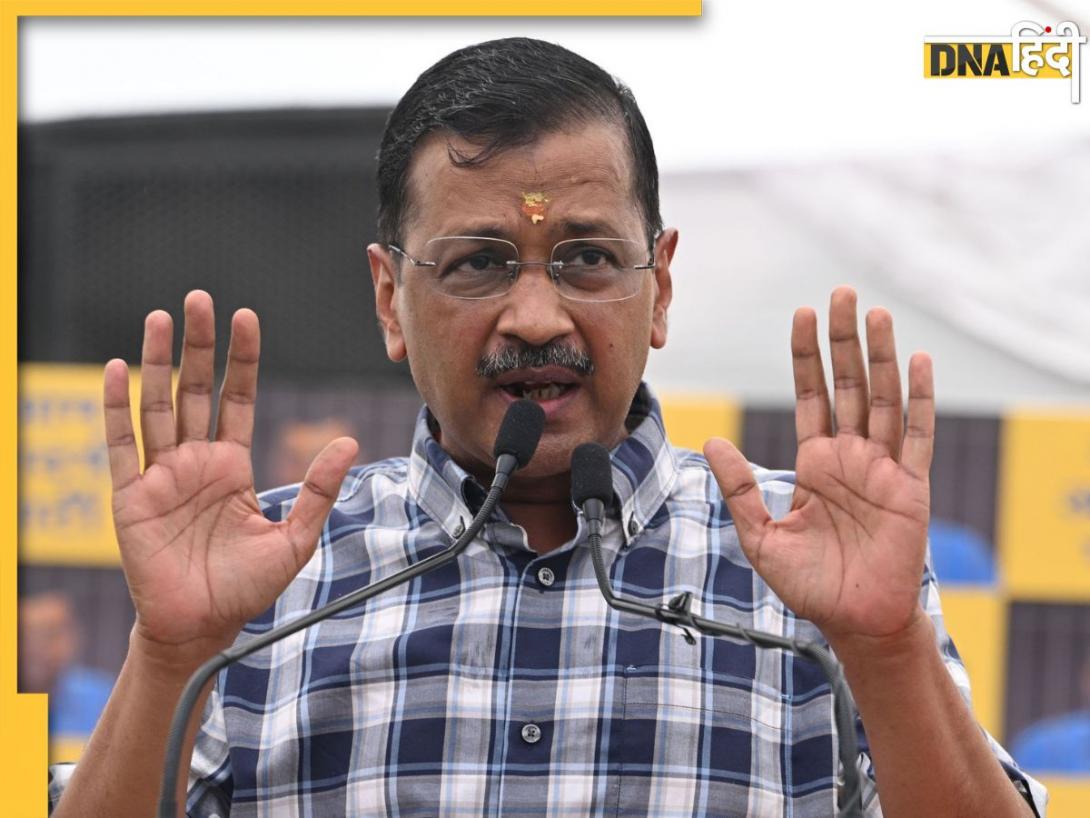

'PM मोदी किस बात पर मांग रहे माफी, भ्रष्टाचार या RSS...' शिवाजी स्टेच्यू विवाद पर बोले राहुल गांधी![submenu-img]() CM अरविंद केजरीवाल की जमानत याचिका पर Supreme Court ने सुरक्षित रखा फैसला

CM अरविंद केजरीवाल की जमानत याचिका पर Supreme Court ने सुरक्षित रखा फैसला ![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

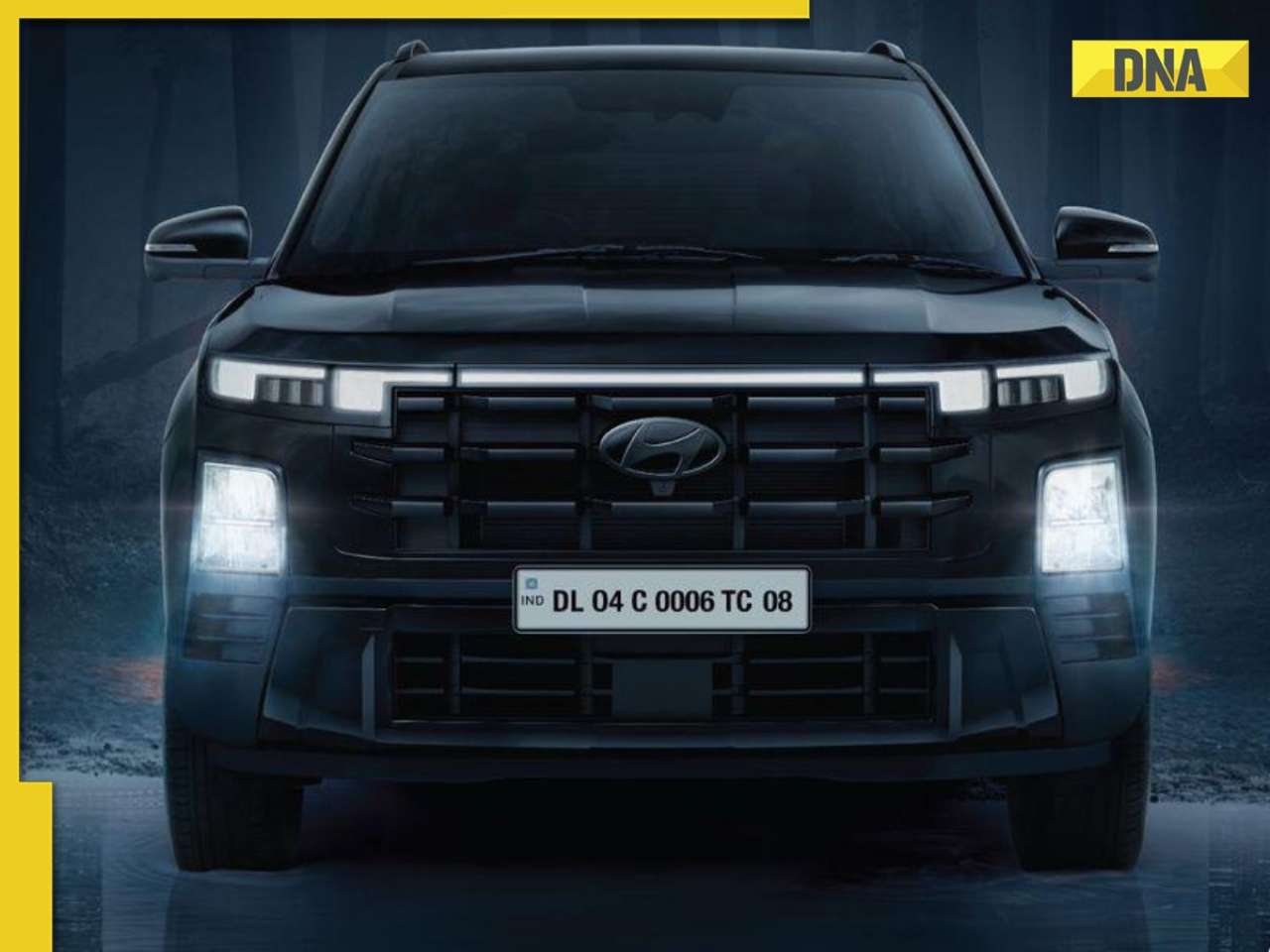

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details![submenu-img]() Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design

Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() After UPSC topper Tina Dabi, IPS Aditya Srivastava's marksheet goes viral, check his scores in different subjects

After UPSC topper Tina Dabi, IPS Aditya Srivastava's marksheet goes viral, check his scores in different subjects![submenu-img]() Meet man who used to sell pens on street, worked as marketer to fund his education, now owns Rs 6000 crore company

Meet man who used to sell pens on street, worked as marketer to fund his education, now owns Rs 6000 crore company![submenu-img]() Meet woman who lost parents at 5, rejected high-paying job offer for UPSC exam, but failed to crack it four times then…

Meet woman who lost parents at 5, rejected high-paying job offer for UPSC exam, but failed to crack it four times then…![submenu-img]() Meet woman, social media queen who prepared for UPSC exam without coaching, but failed to clear it five times and then…

Meet woman, social media queen who prepared for UPSC exam without coaching, but failed to clear it five times and then…![submenu-img]() IIT Bombay minimum salary drop to Rs 4 LPA, average package is...

IIT Bombay minimum salary drop to Rs 4 LPA, average package is...![submenu-img]() Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested

Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here![submenu-img]() Vinesh Phogat Joins Farmers' Protest At Shambhu Border, Answers On Joining Politics | Congress | BJP

Vinesh Phogat Joins Farmers' Protest At Shambhu Border, Answers On Joining Politics | Congress | BJP![submenu-img]() Tripura Floods: 12 Killed, Over 300 Rescued As Heavy Rains Causes Severe Flooding In Tripura

Tripura Floods: 12 Killed, Over 300 Rescued As Heavy Rains Causes Severe Flooding In Tripura![submenu-img]() Kolkata Doctor Murder: Are Indian Rape Laws Enough? Public Opinion On Stricter Measures

Kolkata Doctor Murder: Are Indian Rape Laws Enough? Public Opinion On Stricter Measures![submenu-img]() Meet Hitesh Kumar Sethia, Harvard alumnus to take over as CEO of Mukesh Ambani's company

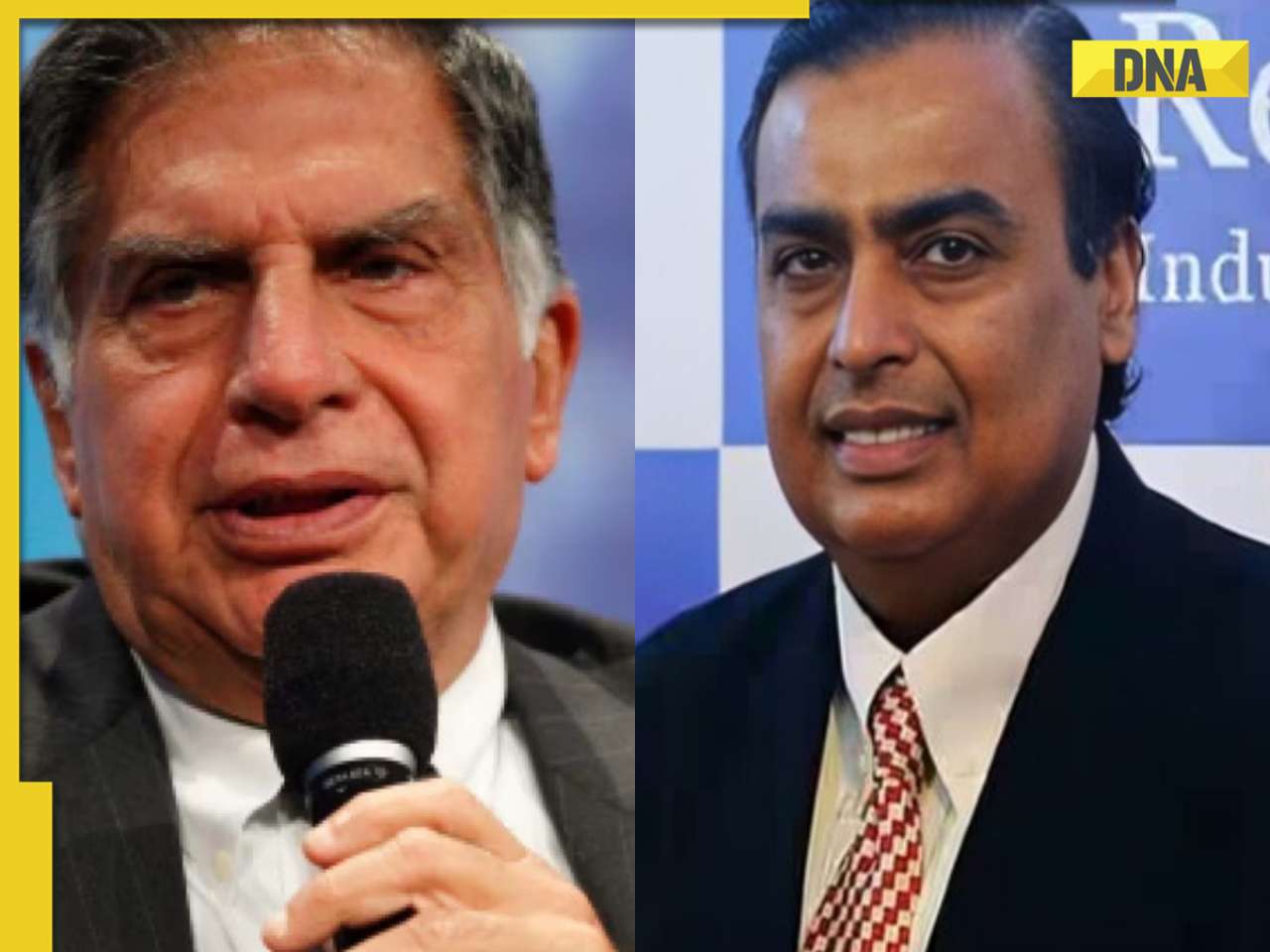

Meet Hitesh Kumar Sethia, Harvard alumnus to take over as CEO of Mukesh Ambani's company![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani vs Ratan Tata: TCS to compete with Jio in...

Mukesh Ambani vs Ratan Tata: TCS to compete with Jio in...![submenu-img]() This is the biggest mall in Pakistan, know who owns it and how much it cost to build it

This is the biggest mall in Pakistan, know who owns it and how much it cost to build it![submenu-img]() Meet man who worked as salesman, then built India's 4th largest pharma company worth Rs 96703 crore, his net worth is...

Meet man who worked as salesman, then built India's 4th largest pharma company worth Rs 96703 crore, his net worth is...![submenu-img]() This man sold balloons on street, then built company worth Rs 57383 crore, Virat Kohli is his…

This man sold balloons on street, then built company worth Rs 57383 crore, Virat Kohli is his…![submenu-img]() Five amazing benefits of drinking 'Haldi-doodh'

Five amazing benefits of drinking 'Haldi-doodh' ![submenu-img]() Indian cinema's most hit jodi did 130 films together, gave 50 hits; not Shah Rukh-Kajol, Amitabh-Jaya, Dharmendra-Hema

Indian cinema's most hit jodi did 130 films together, gave 50 hits; not Shah Rukh-Kajol, Amitabh-Jaya, Dharmendra-Hema![submenu-img]() Good news for Reliance Jio users: Mukesh Ambani offers 5 best cheapest plans for Jio customers

Good news for Reliance Jio users: Mukesh Ambani offers 5 best cheapest plans for Jio customers![submenu-img]() This superhit was offered to Dharmendra, Rajesh Khanna replaced him, worked for free, still earned 10 times his fees

This superhit was offered to Dharmendra, Rajesh Khanna replaced him, worked for free, still earned 10 times his fees![submenu-img]() Meet Ranbir Kapoor's 'niece' who became star at 4, interviewed Virat Kohli, Salman Khan, gave Rs 200 crore hit, now...

Meet Ranbir Kapoor's 'niece' who became star at 4, interviewed Virat Kohli, Salman Khan, gave Rs 200 crore hit, now...![submenu-img]() SEBI employees call for chief Madhabi Puri Buch's resignation over alleged 'toxic' work culture

SEBI employees call for chief Madhabi Puri Buch's resignation over alleged 'toxic' work culture![submenu-img]() 6 dead, 3 injured due to heavy rain, landslides in Nagaland; Rs 4 lakh ex-gratia announced

6 dead, 3 injured due to heavy rain, landslides in Nagaland; Rs 4 lakh ex-gratia announced![submenu-img]() Kolkata doctor rape-murder case: Victim's parents make SHOCKING revelation, say 'police tried to...'

Kolkata doctor rape-murder case: Victim's parents make SHOCKING revelation, say 'police tried to...'![submenu-img]() 'Resume work, leave...': IMA chief Asokan to protesting doctors amid rising uproar over Kolkata rape and murder case

'Resume work, leave...': IMA chief Asokan to protesting doctors amid rising uproar over Kolkata rape and murder case![submenu-img]() Maharashtra: Absconding sculptor of collapsed Shivaji statue arrested in Thane

Maharashtra: Absconding sculptor of collapsed Shivaji statue arrested in Thane

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)