Robert H Frank, a professor of management and economics at the Cornell University in the United States, is the author of The Economic Naturalist.-How Economics Helps Makes Sense of Your World

Why are DVDs sold in much larger packages than CDs, even though the two types of discs are exactly the same size?

CDs come in cases that are 148 millimeters wide and 125 millimeters high. In contrast, DVDs are sold in cases that are 104.5 millimeters wide and 191 millimeters high. A little digging reveals the historical origins of this difference. Prior to the appearance of digital CDs, most music was sold on vinyl discs, which were packaged in close-fitting sleeves that measured 302 millimeters square.

The racks on which vinyl discs were displayed were just wide enough, in other words, to accommodate two rows of CD cases with a divider between them. Making the CD cases a little less than half as wide as the album sleeves they were replacing thus enabled retailers to avoid the substantial costs of replacing their storage and display racks. Similar considerations seem to have driven the decision regarding DVD packaging.

Before DVDs became popular, most film rental stores carried videotapes in the VHS format, which were packaged in form-fitting boxes that measured 135 mm wide and 191 mm high. These videos were typically displayed side by side with their spines out. Making DVD cases the same height enabled stores to display their new DVD stocks on existing shelves while consumers were in the process of switching over to the new format.

Making the DVD package the same height as the VHS package also made switching to DVDs more attractive for consumers, since they could store their new DVDs on the same shelves they used for their VHS tapes.

Why are whales in danger of extinction, but not chickens?

Seldom does a year pass without a street demonstration by environmental activists decrying international hunting that threatens extinction for many large marine mammal species. Yet to my knowledge there has never been a demonstration exhorting us to save chickens.

Why not? The short answer is that chickens have never been an endangered species. But that just raises the question of why one species is endangered and another not. Whale populations have been dwindling because no one owns whales.

They swim in international waters, and several nations have refused to respect the international treaties that have attempted to protect them. Japanese and Norwegian whalers understand perfectly well that their current practices threaten the survival of whales and hence their own livelihood. But each whaler also knows that any whale he does not harvest will be taken by someone else.

Thus no whaler stands to gain from self-restraint. In contrast, most chickens in the world are owned by someone. If you kill one of your chickens today, that is one less chicken you will own tomorrow. If chicken farming were your livelihood, you would have strong incentives to balance the number of birds you send to market and the number of new chicks you acquire.

Chickens and whales are both economically valuable. The fact that people enjoy secure property rights in chickens but not in whales explains why the former are secure and the latter are endangered.

Why are physically attractive people more intelligent than others, on average?

Research has shown that people who are regarded as physically attractive also tend to be seen as more intelligent. And it has often been noted that attractive children tend to receive higher grades in school.

Although the later finding has been interpreted as evidence of teacher bias, an economic analysis of the informal market for marriage partners suggests that better-looking children may actually be smarter.

Evolutionary psychologists Satoshi Kanazawa and Jody Kovar, for example, offer persuasive evidence for the following four propositions: 1) More intelligent men tend to achieve higher social stauts and higher incomes. 2) Men generally regard physically attractive women as more desirable marriage partners. 3) Women generally regard men with higher incomes and higher social status as more desirable marriage partners. 4) Both intelligence and physical attractiveness are traits with significant heritable components. If the first three propositions are true, then it follows logically that relative attractive women will pair up disproportionately with relatively intelligent men.

And if both beauty and intelligence are heritable, then the offspring of such unions will tend to display above-average value of both traits. In short…the hypothesis that beauty and brains go together does not appear far-fetched.

Why do ‘almost new’ used cars sell for so much less than brand new ones?

When a new car leaves the showroom, it can lose 20% or more of its value almost overnight. Considering that modern cars typically have useful lives of more than 200,000 miles, why should a few miles on the odometer cause a vehicle’s price to plummet? Part of the price drop reflects the difference between wholesale and retail prices.

When a new car is first sold, the buyer pays a retail price, which can be as much as 15% higher than what the dealer paid for it. When a private consumer buys a car and decides to sell it immediately, he becomes an amateur car dealer. He would like to sell the car at close to its original retail price, of course.

But in attempting to do so, he must compete with a host of professional dealers who have attractive, well-lighted showrooms and employ skilled salespersons and mechanics. And because it is easier for professional dealers to attract interested car buyers, it is expected that the offerings of private sellers will command lower prices.

But there is a second important reason that nearly new used cars sell for so much less than brand-new ones. Because of variations in manufacturing and assembly processes, not all new cars are equally reliable when they come off the assembly line. Such differences in reliability are amplified by differences in the care with which owners maintain their vehicles.

Although some almost new cars are lemons, not even trained mechanics can distinguish them for their more reliable counterparts. The upshot is that the owner of a used car generally knows much more about it than a prospective buyer does…So people would be unwilling to buy used cars unless their price was deeply discounted.

Why do stock analysts seldom recommend selling a particular company’s stock?

Many investors rely on the recommendations of professional stock analysts. Yet studies show these recommendations to be astonishingly one-sided. In 2000, for example, there were 28,000 recommendations on US companies by brokerage house analysts, of which more than 99% were either strong buy, buy, or hold. Analysts recommended selling the stocks of individual companies less than 1% of the time that year.

Yet a substantial share of American companies saw their stock prices decline in 2000, many of them by more than half. It is tempting to say that analysts in 2000 fell victim to the same “irrational exuberance” that affected investors generally during the boom years of the late 1990s. But research shows that analyst recommendations show a similar bias toward optimism in other years as well.

A plausible source of this bias is suggested by an examination of the costs and benefits confronting stock analysts as they formulate their recommendations. Consider a stock that is covered by five different analysts. Each wants to make an accurate prediction of how the stock’s price will move during the coming months; but each also wants to maintain a good relationship with the company being evaluated, often a client or a potential client of her employer. Under the circumstances, the analyst faces strong incentives to consider the likely recommendations of the other four analysts before formulating her own position.

After all, she knows that the cost of being wrong depends in part on the recommendations made by the other four analysts. From the outset, she knows that the recommendations of others are likely to be biased at least slightly in favor of buying, because analysts’ employers have an interest in currying favour with evaluated companies. At one extreme, if all five recommend buy and the company’s stock price then falls, the analyst knows her vulnerability to criticism would be limited by the fact that the forecast error was widespread.

What happens if the analyst recommends a sell?

Alternatively, if she recommends sell while the other four recommend buy and the company’s stock price then goes up, she becomes a triple loser. Not only was her recommendation wrong, but her error was conspicuous, since rival analysts got it right. Adding insult to injury, her employer would suffer the ill will of a potential client. All things considered, the safest bet for the individual analyst is to herd with the expected recommendations of other analysts. Each understands that the interests of other analysts’ employers’ are, like those of her own, better served through buy recommendations. In addition, other analysts are making forecasts not only of how the company’s stock will perform but also of what other analysts will recommend. So it is easy to see why the analyst’s safest bet is a buy recommendation. But as careful investors eventually learn, a buy recommendation conveys little useful information about a stock’s future price.

Does the world have too many hedge fund managers?

What are the career aspirations of the nation’s most accomplished and ambitious students these days? I haven’t seen a formal survey, but a rapidly growing percentage of the best students I teach say they want to manage hedge funds or private equity firms.

Why is that?

Little wonder. This market is what economists call a winner-take-all market — essentially a tournament in which a handful of winners are selected from a much larger field of initial contestants. Such markets tend to attract too many contestants for two reasons. The first is an information bias. An intelligent decision about whether to enter any tournament requires an accurate estimate of the odds of winning. Yet people’s assessments of their relative skill levels are notoriously optimistic. Surveys show, for example, that more than 90% of workers consider themselves more productive than their average colleague. This overconfidence bias is especially likely to distort career choice because, in addition to the motivational forces that support it, the biggest winners in many tournaments are so conspicuous. For example, NBA (National Basketball Association, the US league) stars who earn eight-figure salaries appear on television several nights a week, whereas the thousands who failed to make the league attract little notice.

So hedge fund managers are also more visible?

Similarly, hedge fund managers with 10-figure incomes are far more visible than the legions of contestants who never made the final cut. When people overestimate their chances of winning, too many forsake productive occupations in traditional markets to compete in winner-take-all markets.

Any other reason?

A second reason for persistent overcrowding in winner-take-all markets is a structural problem called “the tragedy of the commons.” This problem helps explain, for instance, why we see too many gold prospectors, an occupation that has much in common with prospecting for corporate deals. In the initial stages of exploiting a newly discovered gold field, adding another prospector may significantly increase the total amount of gold found. Beyond some point, however, additional prospectors contribute little. The gold found by a newcomer to a crowded field is largely gold that would have been found by existing searchers.

Can you elaborate on that?

A simple numerical example helps illustrate why private incentives often lead to wasteful overcrowding under these circumstances. Consider a man who must choose whether to work as an engineer for $100,000 or become a prospector for gold. Suppose he considers the nonfinancial aspects of the two careers equally attractive and expects to find $110,000 in gold if he becomes a prospector, $90,000 of which would have been found in his absence by existing prospectors. Self-interest would then dictate a career in prospecting, since $110,000 exceeds the $100,000 engineering salary. But because his efforts would increase the total value of gold found by only $20,000, society’s total income would have been $80,000 higher had he instead become an engineer.

What’s that got to do with hedge fund managers?

Similar incentives confront aspiring portfolio managers. Beyond some point, adding another highly paid manager produces little increase in industry commissions on managed investments.

As in a crowded real estate market, the additional manager’s commissions come largely at the expense of commissions that would have been generated by existing managers. So here, too,

private incentives result in wasteful over-crowding.

![submenu-img]() Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa

Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'

Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...

Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() Aparajita Bill पर ममता बनर्जी को झटका, राज्यपाल ने कमियां गिना राष्ट्रपति के पास भेजा

Aparajita Bill पर ममता बनर्जी को झटका, राज्यपाल ने कमियां गिना राष्ट्रपति के पास भेजा![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट

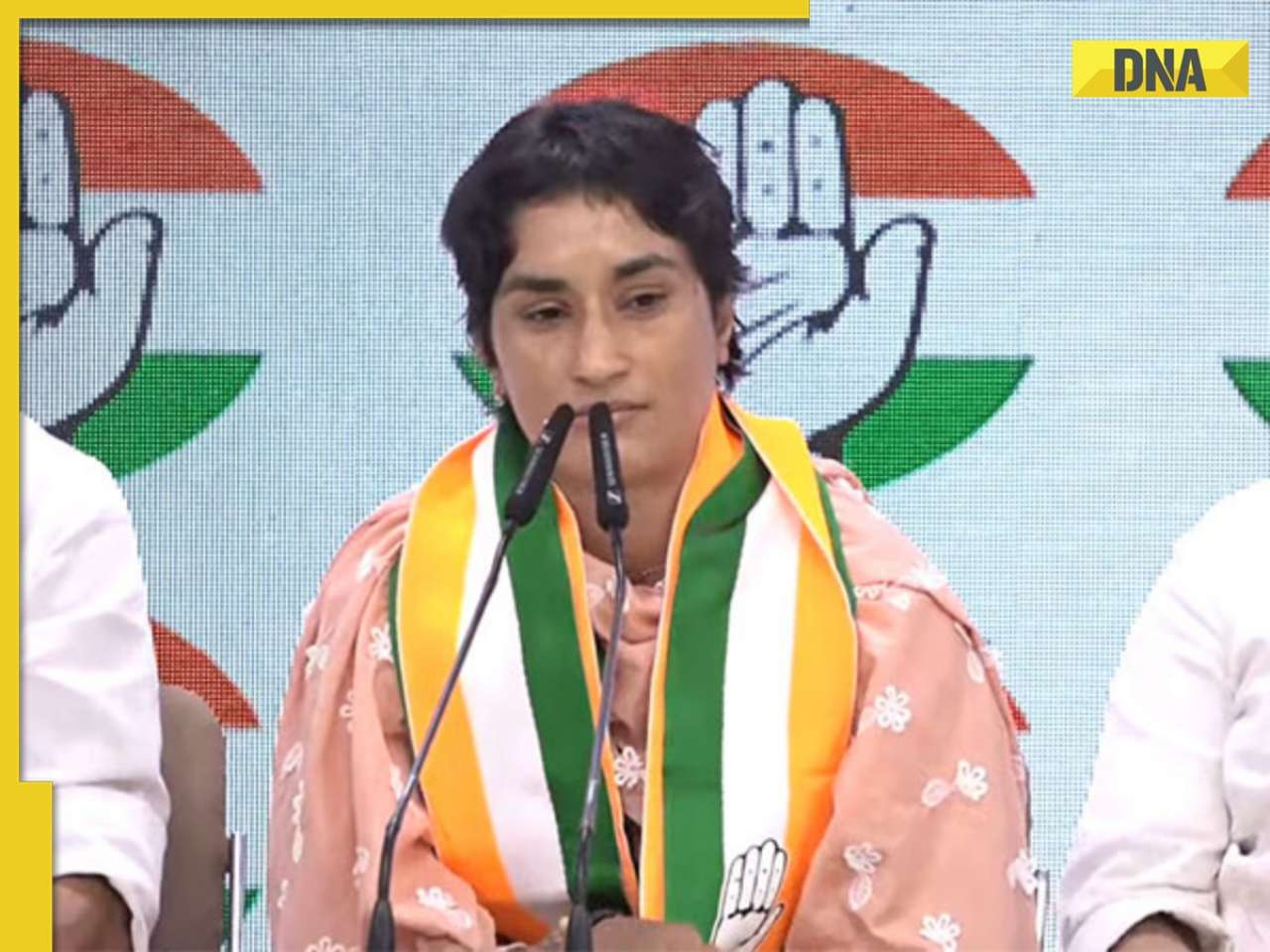

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट![submenu-img]() Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल

Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल![submenu-img]() Viral Video: Indigo की फ्लाइट में बंद हो गया एसी, गर्मी से परेशान यात्री हो गए बेहोश

Viral Video: Indigo की फ्लाइट में बंद हो गया एसी, गर्मी से परेशान यात्री हो गए बेहोश ![submenu-img]() Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट

Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details![submenu-img]() Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design

Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects

UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects![submenu-img]() Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...

Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…

Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…![submenu-img]() Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed

Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed![submenu-img]() 'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project

'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project![submenu-img]() Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure

Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure![submenu-img]() Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested

Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...

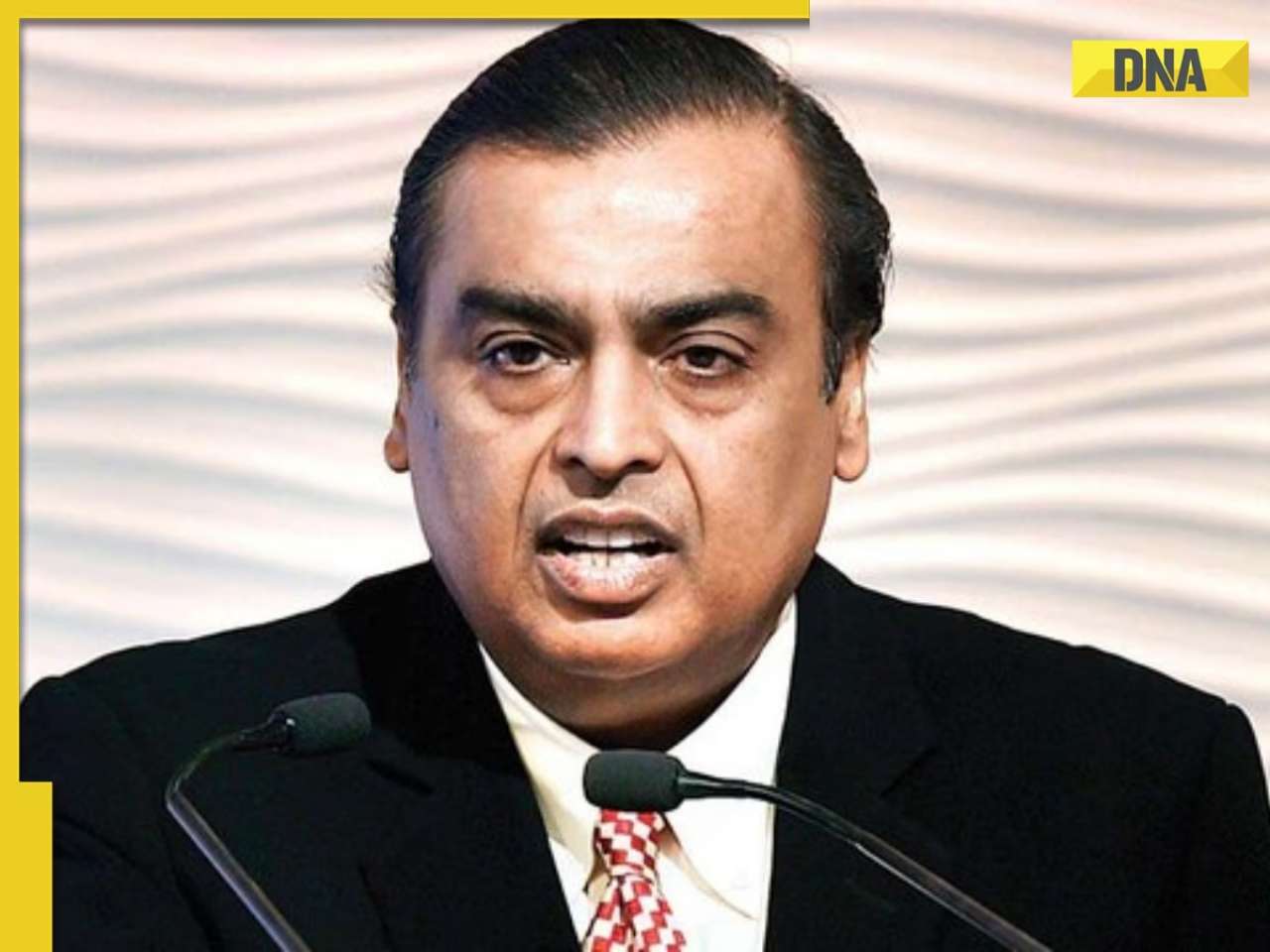

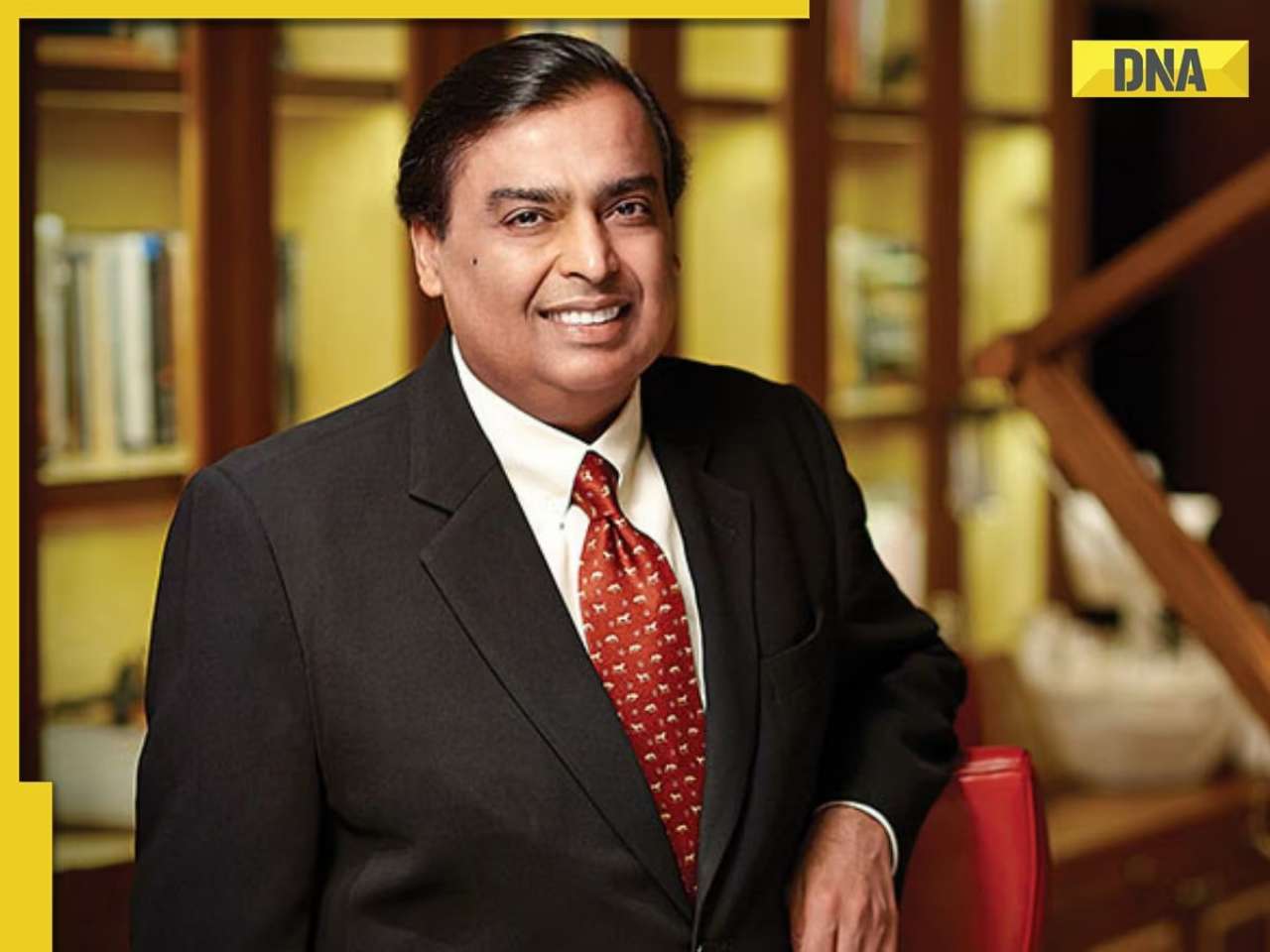

Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...![submenu-img]() NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works

NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...

Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...![submenu-img]() This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection

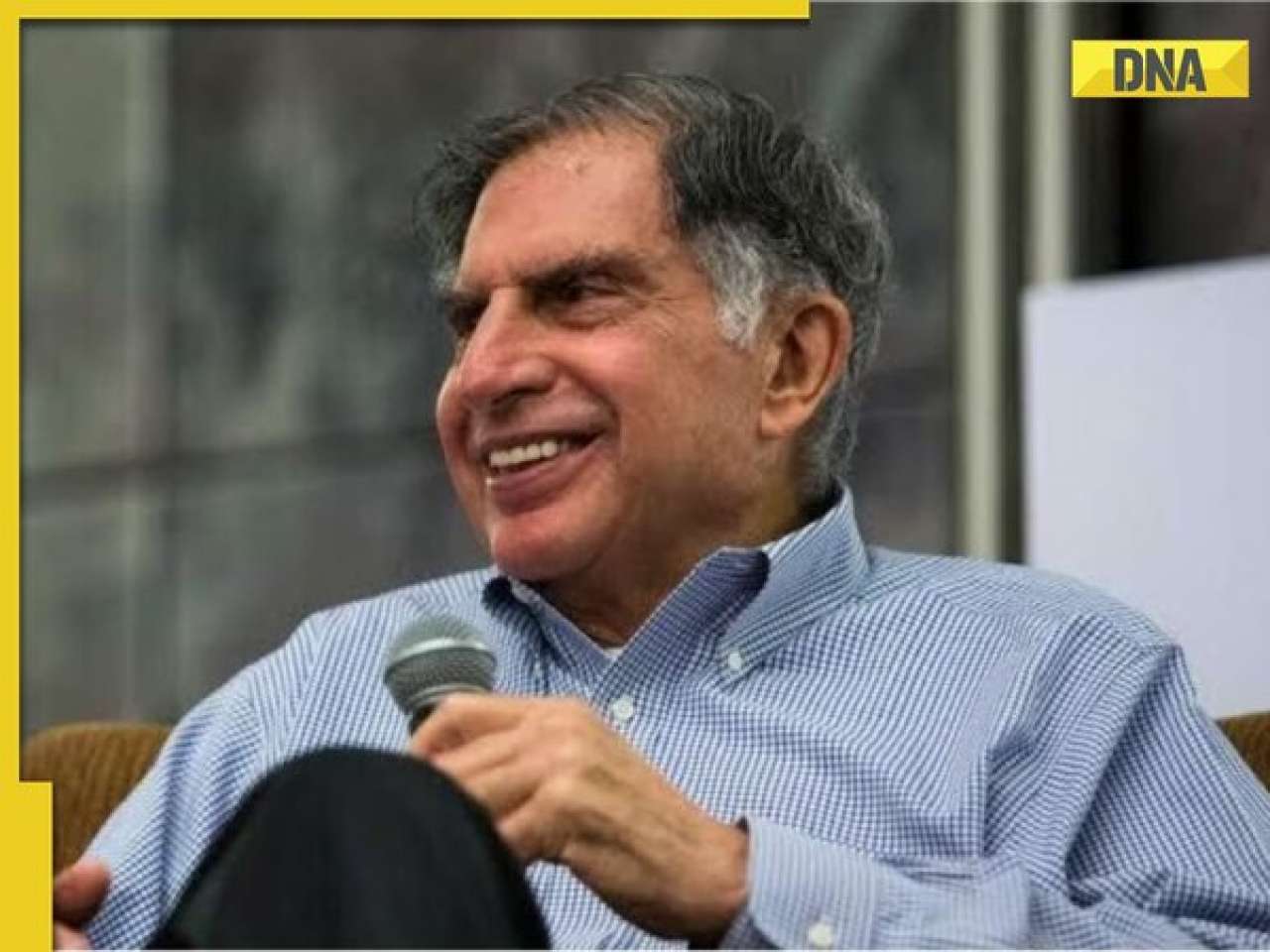

This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection![submenu-img]() Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...

Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...![submenu-img]() From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months

From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...

Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...![submenu-img]() Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival

Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival![submenu-img]() Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body

Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body ![submenu-img]() Active players with most centuries in international cricket

Active players with most centuries in international cricket ![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() 'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP

'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP![submenu-img]() India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...

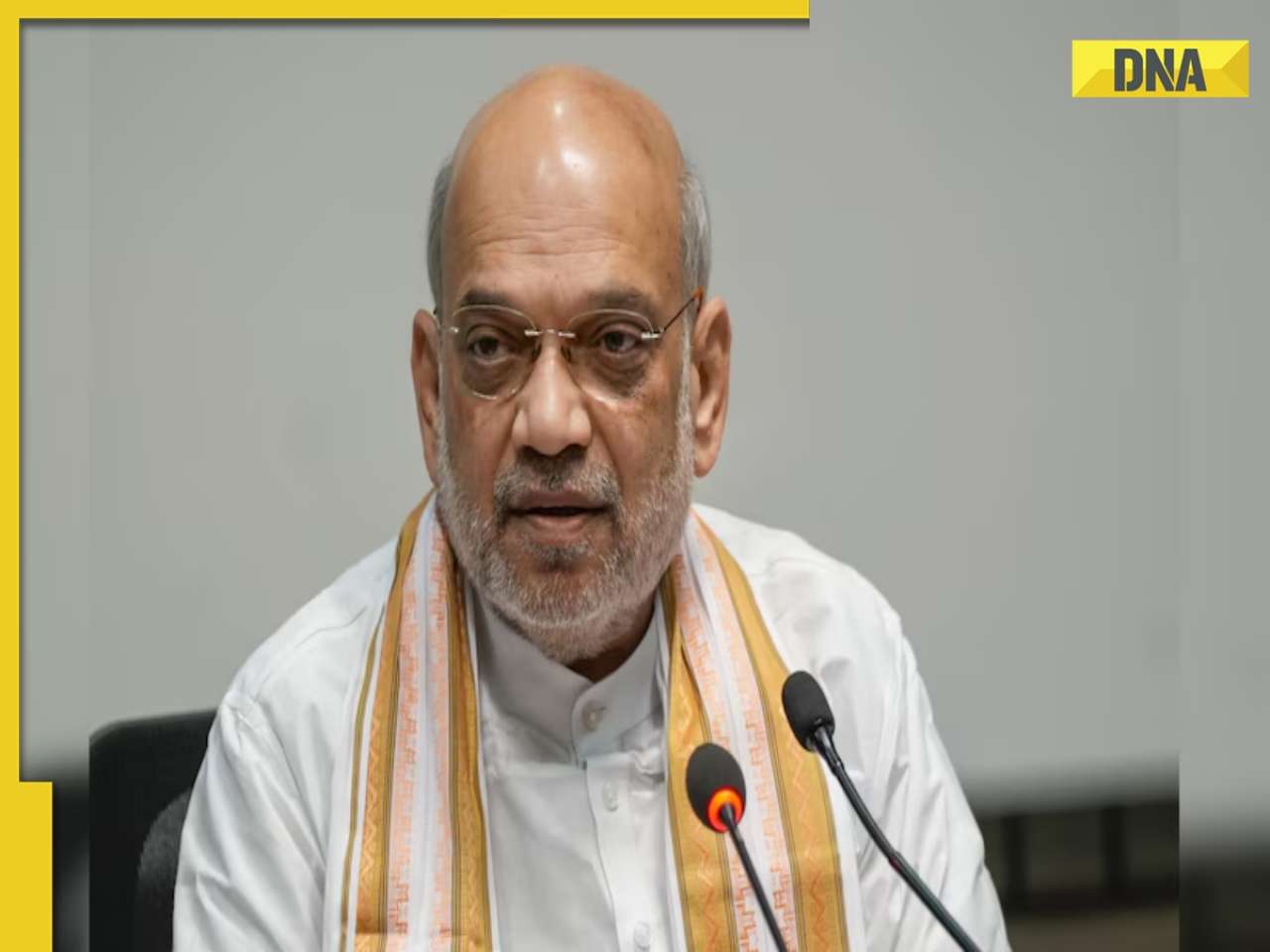

India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...![submenu-img]() Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)