The administration of flat tax is simple. Because every rupee is taxed at the same rate, the tax collector need not know who is earning how much, says A V Vedpuriswar

In many countries, the tax system has become so complicated that the need to simplify has become urgent. Between 2000 and 2003, seven OECD (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development) countries cut the number of tax brackets. A radical idea which is being hotly discussed today is flat tax, a system that taxes all entities in a class at the same rate (as a proportion of income). In contrast, in a graduated, or progressive scheme, people with higher incomes pay tax at a higher rate than those with lower income.

In 1994, Estonia became the first country in Europe to introduce a “flat tax” on personal and corporate income, with a single uniform rate of 26%. Latvia (25%), Lithuania, Russia (with a rate of 13% on personal income) Slovakia (19% on personal and corporate income), Ukraine (13%), Serbia (14%), Georgia (12%), Romania (16%) have followed subsequently.

The flat-tax movement has taken off in a big way in these former communist countries as they were starting from scratch, or nearly so, in choosing a tax code. So opting for the simplest, most efficient system available was the natural thing to do.

According to conventional wisdom, “progressive” tax systems are better as they tax the rich more heavily, compared to the poor. But progressive tax systems have not been all that successful in introducing an element of fairness. In New Zealand, for example, only the richest tenth of households pay more under the country’s progressive income tax system than they would under a 25% flat tax. And whatever fairness gained may not be worth all the extra complexity resulting from many tax brackets and exemptions. In the United States, the costs of compliance, administration and enforcement have been estimated between 10% and 20% of revenue collected or 25-50% of the government’s budget deficit.

In contrast, the administrative elegance of a pure flat tax is phenomenal. Because every rupee is taxed at the same rate, the tax collector need not know who is earning how much. The tax authorities can simply withhold, say, 20% of a company’s payroll.

The flat tax can come in different versions. Russia has imposed a single 13% tax rate on all personal income. But it has a different rate for corporate profits. Slovakia’s flat tax, by contrast, covers both personal income and corporate income, as well as VAT, a move aimed at discouraging tax arbitrage. For example, it was earlier quite common for people in Slovakia to declare themselves self-employed, even when they were salaried employees. Their lunch would be counted as a business expense while their wages would be taxed as profits!

There is increasing evidence that a flat tax can yield good results. In Estonia, just before the introduction of flat tax, general government revenues were 39.4% of GDP; in 2002, they were 39.6%. Estonia now plans to cut its flat tax from 26% to 20% by 2007.

The most impressive achievement has been recorded in Russia, whose tax arrears amounted to 34% of collections in 1997. Russia’s bigger enterprises evaded an estimated 29% of their taxes and paid another 63% in kind, with goods and services often of little value to the government. In lieu of $80,000 in taxes, one company reportedly offered the government 10 tonnes of toxic chemicals!

On January 1, 2001, Russia combined its 12%, 20% and 30% personal income tax bands into a single, uniform 13% rate. A year after the reform, the personal income tax was raising almost 26% more revenue in real terms. In the year before the flat tax, Russians in the two higher tax brackets reported only 52% of their income to the tax authorities. In 2001, these same households reported 68%.

In our country too, we need radical tax reforms. Our Income Tax Act despite some reforms in the past 20 years remains as complicated as ever. Measures like the fringe benefits tax introduced in the recent budget are clearly a retrograde step. A flat tax may be the need of the hour. The leftists and socialists who have a significant say in policy formulation today may describe it as anti-people! But the sheer convenience and ease of administration of a flat tax system hold out the promise of a clean and transparent tax system, which our country badly needs.

The author is dean, Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts of India (ICFAI), Hyderabad. email: ved@icfai.org

![submenu-img]() Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa

Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'

Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...

Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() Aparajita Bill पर ममता बनर्जी को झटका, राज्यपाल ने कमियां गिना राष्ट्रपति के पास भेजा

Aparajita Bill पर ममता बनर्जी को झटका, राज्यपाल ने कमियां गिना राष्ट्रपति के पास भेजा![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट

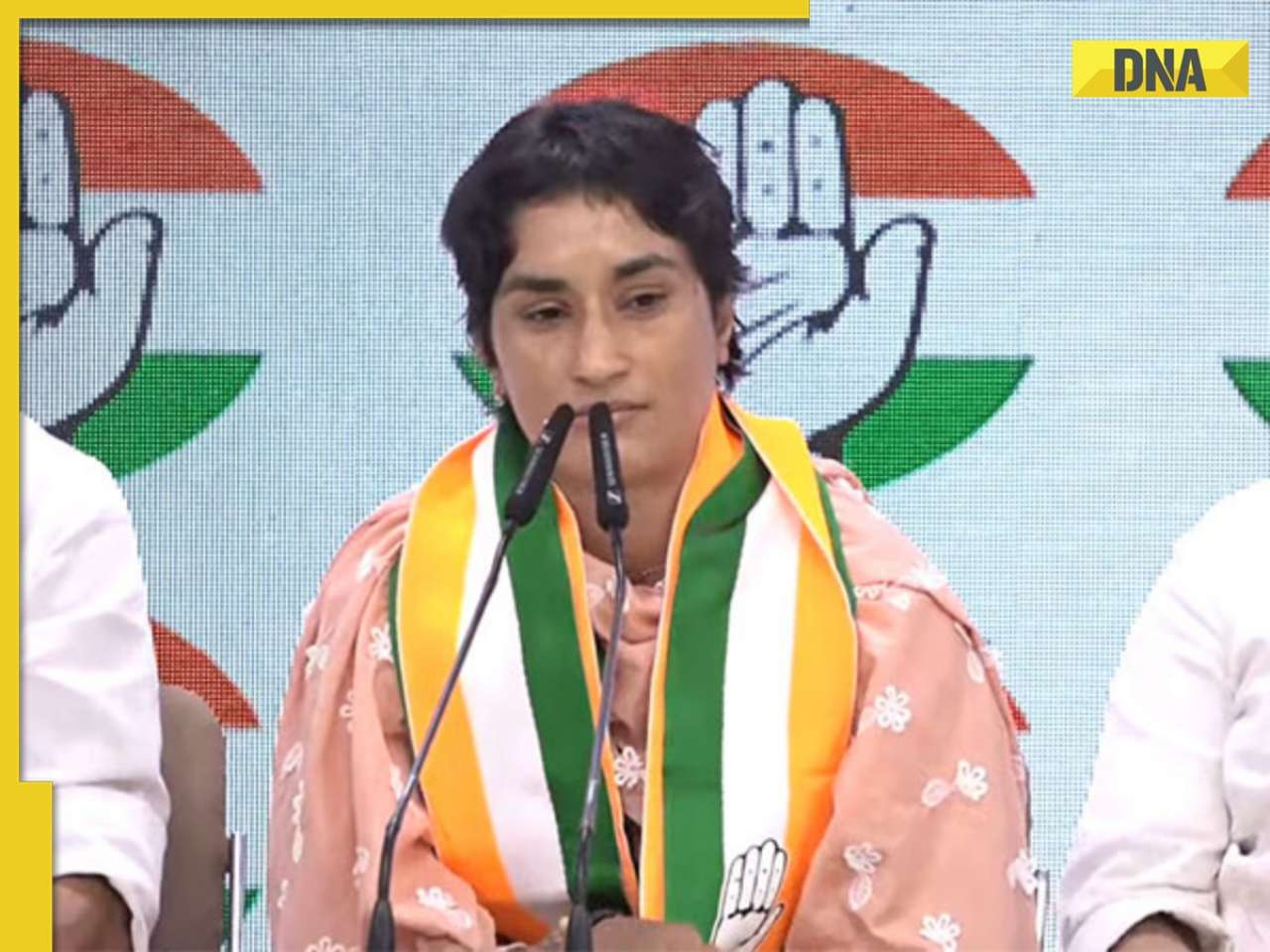

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट![submenu-img]() Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल

Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल![submenu-img]() Viral Video: Indigo की फ्लाइट में बंद हो गया एसी, गर्मी से परेशान यात्री हो गए बेहोश

Viral Video: Indigo की फ्लाइट में बंद हो गया एसी, गर्मी से परेशान यात्री हो गए बेहोश ![submenu-img]() Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट

Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details![submenu-img]() Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design

Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects

UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects![submenu-img]() Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...

Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…

Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…![submenu-img]() Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed

Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed![submenu-img]() 'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project

'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project![submenu-img]() Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure

Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure![submenu-img]() Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested

Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here

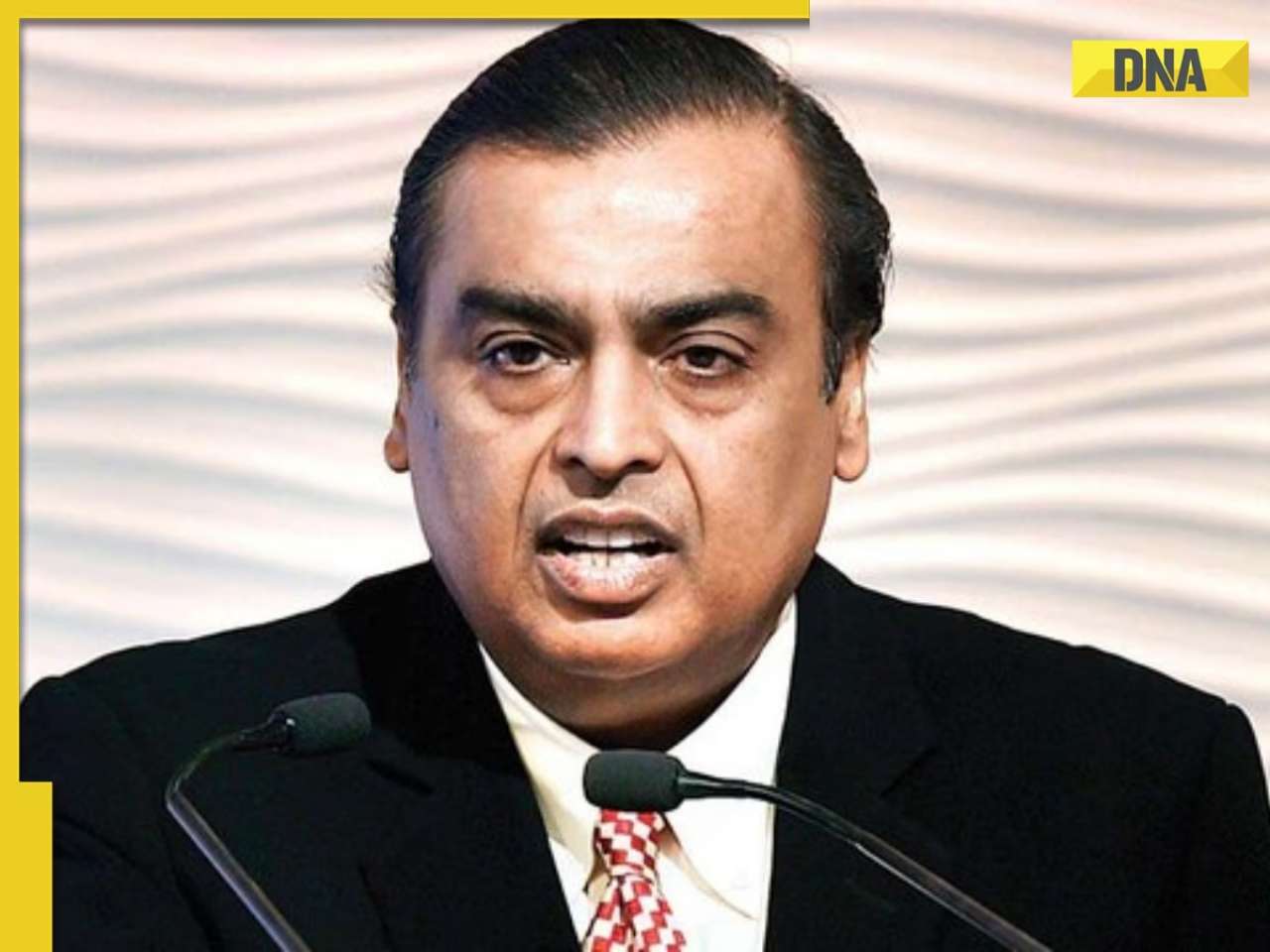

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...

Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...![submenu-img]() NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works

NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...

Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...![submenu-img]() This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection

This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection![submenu-img]() Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...

Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...![submenu-img]() From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months

From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...

Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...![submenu-img]() Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival

Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival![submenu-img]() Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body

Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body ![submenu-img]() Active players with most centuries in international cricket

Active players with most centuries in international cricket ![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() 'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP

'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP![submenu-img]() India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...

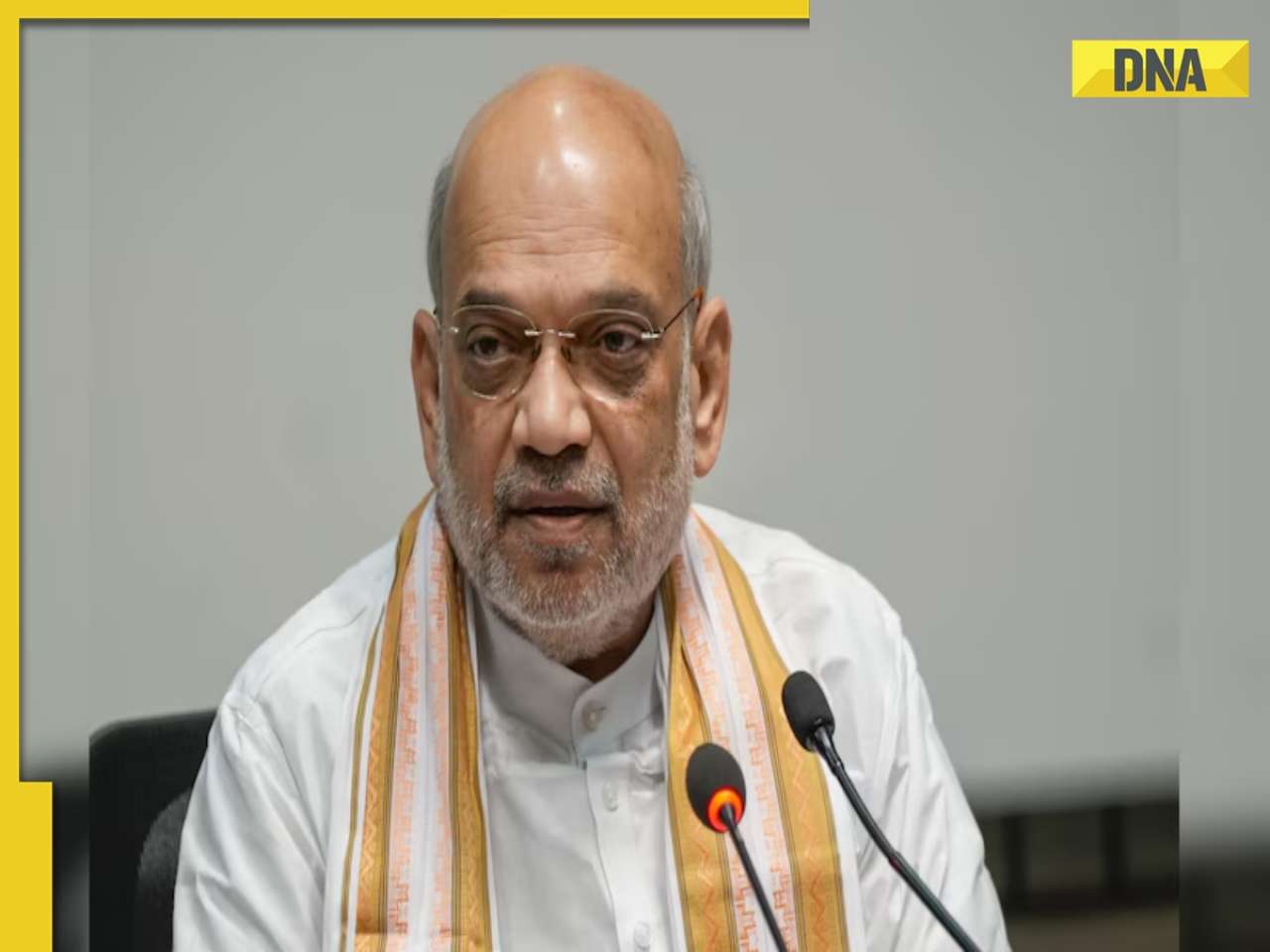

India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...![submenu-img]() Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)