The NCPA last week screened a recording of Danny Boyle's Frankenstein after the show was performed in London.

The sky was spitting rain as we stepped out of office. Providentially, a taxi — a rattling old thing held together with duct tape and hope — came spluttering to our rescue. We got in, and began our slow crawl through the metal-choked streets of Mumbai to an evening of wonderful incongruities. Sukha bhel in office, coughing radiators, mud-splattered trouser cuffs, wine, canapés and high-theatre (Danny Boyle’s smash-hit Frankenstien, all the way from the National Theatre in London).

Mingling of experiences

This mingling of the plebian and the privileged is presumably what David Sabel, head of digital media at the National Theatre, had in mind when he set out to bring London’s West End to those of us prevented by geography and finance from going there. But would it live up to the promise? Can watching a play on screen — no matter the number of cameras filming it, no matter the number of fancy arcs and pirouettes they make — ever be as good as being there?

Apparently not. “Something is lost, when you approach it this way (seeing it on screen)”, admits Sabel. “It’s not the best possible experience, but there are advantages though. You get great intimacy with the performers, you can see the nuances of their performance, it’s like having the best seats in the house.” Well, it was time to put his claims to the test.

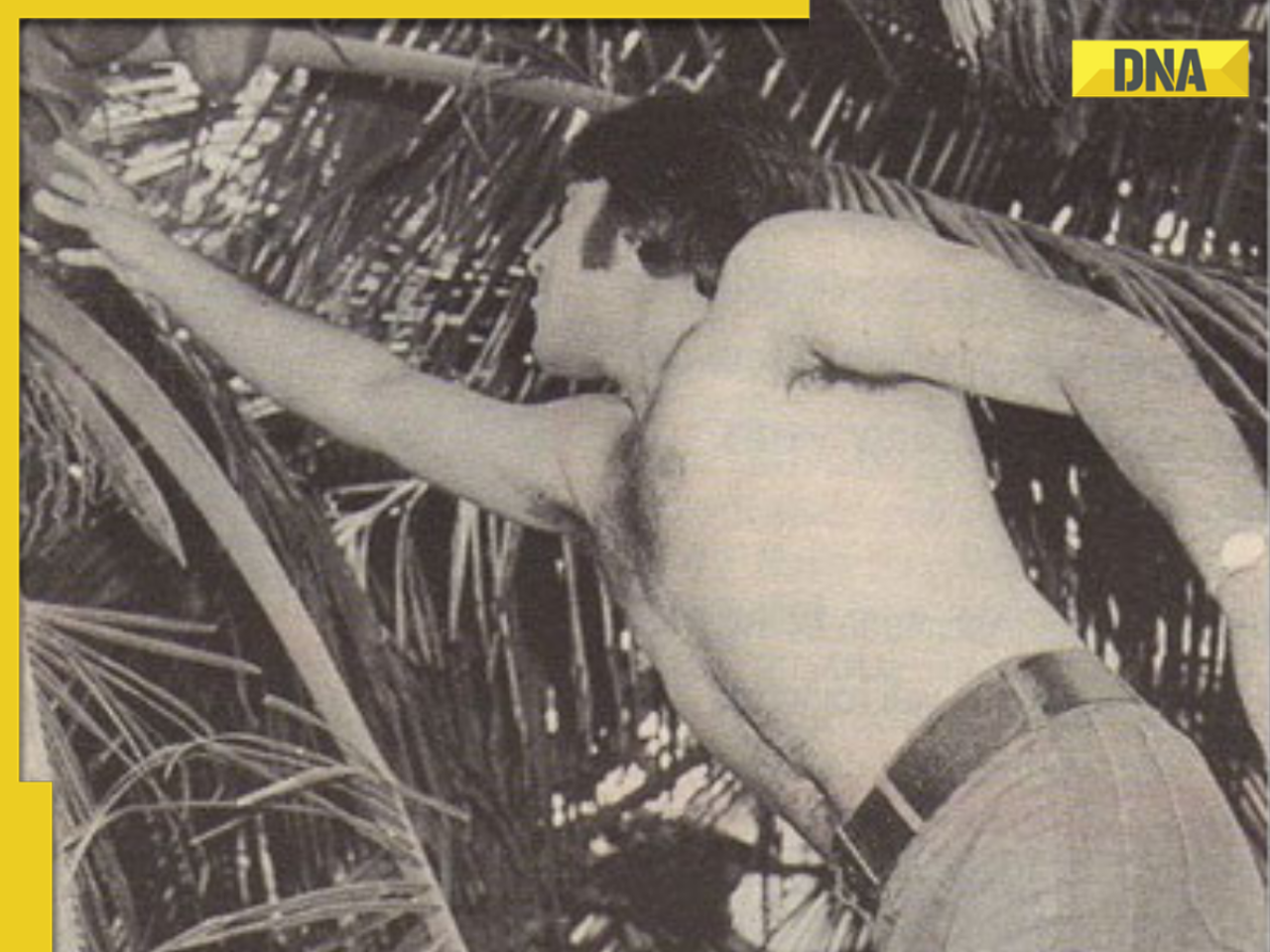

An awkward opening speech by an absurdly well-coiffed Anil Kapoor began the proceedings. It was followed by a short documentary about the play and its players began the proceedings. It was pretty much par for the course stuff. The basic hypothesis of Frankenstein is that human beings cannot be trusted to govern that which is forged by their own passions and intellect. It’s a time-tested, fear-inspiring formula repeatedly explored to great financial success in movies such as the Terminator or The Matrix series.

Dear, to inject freshness into a done-to-death story-line, approaches the subject from the point of view of the monster, which neither the original text nor the numerous film adaptations have done. It’s an interesting tack that is engaging for a while before it becomes predictable in its execution. Abandoned by his creator, shunned by society for his appearance, the monster learns hate and deceit “at the feet of my master”, and in turn, he becomes a true monster inside and out.

It is not particularly thought-provoking stuff. Missives against intolerance and meditations on human frailties have been done before, and done better. Dear contrives to spell out the nuances of thought in such obvious terms that one cannot help but feel a little patronised. In the scene where the monster rapes and murders Elizabeth, Dr. Frankenstein’s wife, Benedict Cumberbatch (as Frankenstein) goes to great lengths to make obvious the duality of his impulses, his rational urge for revenge, and his subsequent regret, firmly imposing the realisation on the audience. There is not really much chance for interpretation or discovery.

To be or not to be there

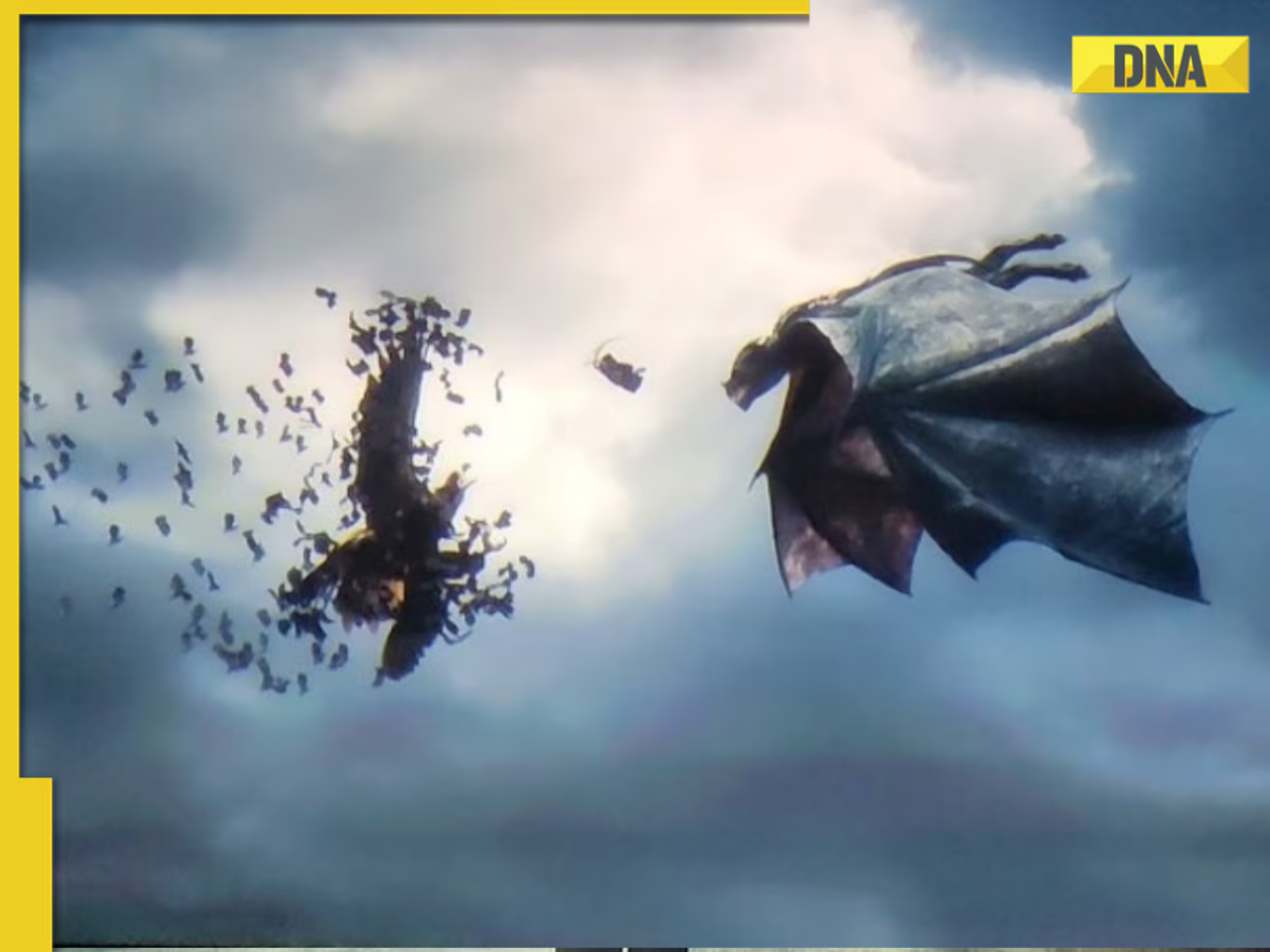

However, what the writing lacks is more than made up in stagecraft and performance. And much of the credit for Frankenstein’s success should go to Danny Boyle, Cumberbatch and Johnny Lee Miller (as Dr Frankenstein). Cumberbatch’s monster is an absolute delight. The opening minutes, when the monster tears out of the ghostly illuminated womb of his master’s creation, and a rough cobble of limbs and organs thrash violently around the stage, trying to find purpose and unity, is disturbing to watch for its physical intensity. Cumberbatch’s naturally elvish features, even covered by thick grotesque scars, allude to the man the monster once was. The audience’s sympathy for the creature — which is essential in making the narrative work — is almost a given with Cumberbatch’s monster.

We, unfortunately, didn’t have an opportunity to see Miller in the monster’s role, but if reviews are anything to go by, his performance has been lauded in just as lavish terms.

The other hero of the show is the stagecraft. A huge conical mass of light-bulbs hangs imposingly on the stage, a massive orange stalactite of energy. One cannot even begin to imagine the wonder of actually sitting in the National Theatre watching it light up in its vast and luminescent glory. There is a definite difference in perspective, for the audience at the show and the audience watching the screening. It’s not merely the addition of a fifth wall, but also the visual perspective that multiple moving cameras provide. In a dark hall at the NCPA, sitting thousands of miles away, we were catching every subtle facial expression that no one beyond the first few rows in the theatre can hope to.

The cameras also alter the visual language of the play. In the scene where the monster first encounters rain and revels joyously in its sensation, the camera is placed in a bird’s eye view, which elevates the audience to a God-like status, looking down at Cumberbatch. Later, when it cuts to a long shot, we see what the audience sees, from a level similar to that of the actor, which inspires solidarity and sympathy.

These are issues to parse over. Theatre is at a very interesting juncture. Technology has made it possible to widen its audience beyond the confines of the hall. Filming is no longer an after-thought or intrusion, plays are being blocked, rehearsed and designed specifically to cater to the presence of the camera. Maybe in the future they will be written with the camera in mind. The lines between cinema and theatre will blur further.

Whether this bodes well or ill for theatre is open to debate. However, one thing is clear: no amount of fancy camera work can be a substitute for the actual experience of being there. As the screen went blank after the curtain calls, there was a strange sense of loss. The initial shock gave way to an overwhelming urge to be there, to feel the atmosphere charged with applause and wonder, heavy with the sweat of the actors. As we made our way out after the show, I happened to mention this to a friend, and he quipped, “It’s better than nothing, right?” Right.

Frankenstein is showing today at the NCPA at 4 pm and 7 pm.

![submenu-img]() Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa

Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'

Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...

Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

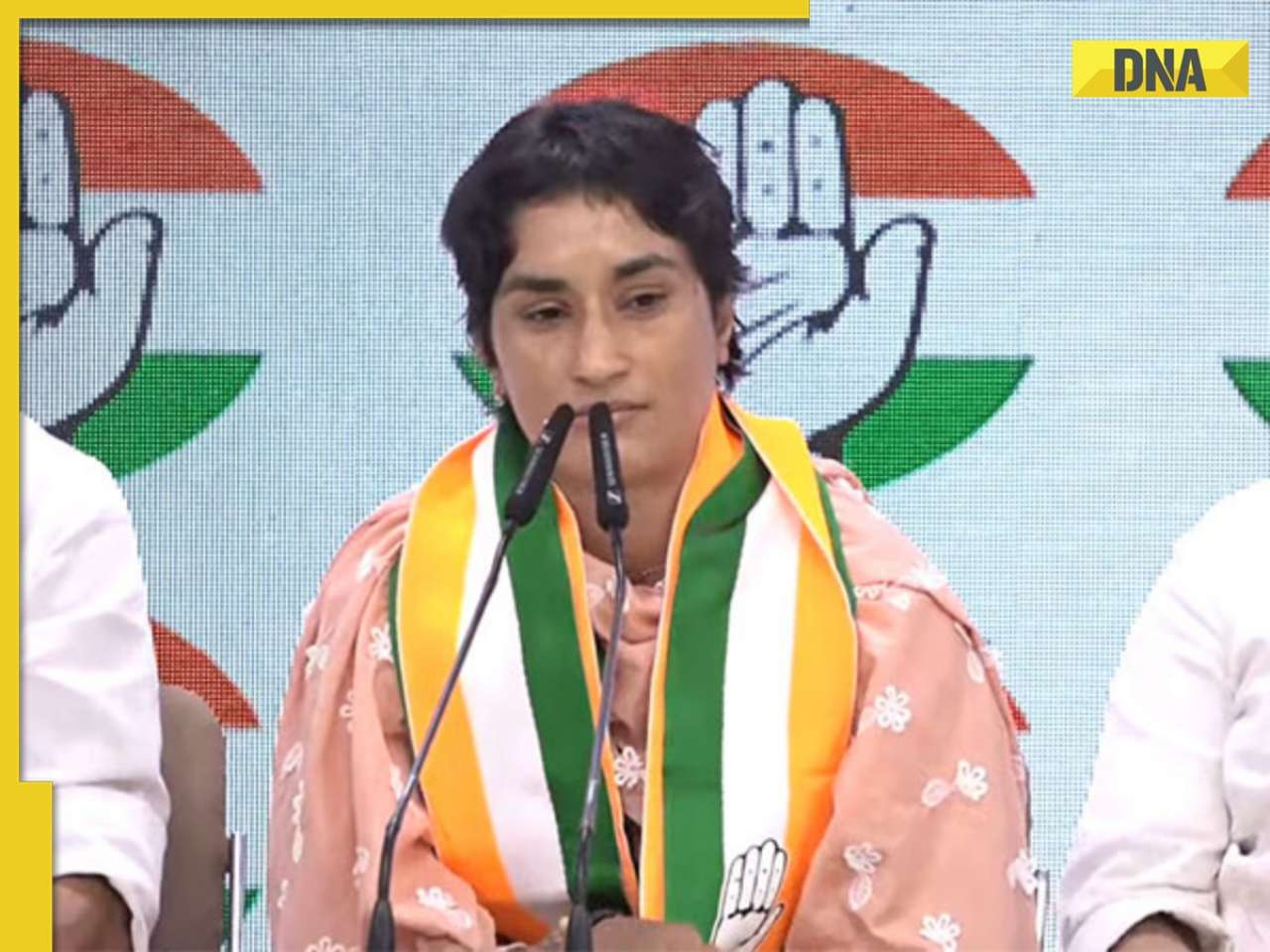

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट![submenu-img]() Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल

Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल![submenu-img]() Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट

Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट![submenu-img]() J-K विधानसभा चुनाव: 'आर्टिकल 370 को हम कभी वापस नहीं आने देंगे', अमित शाह ने जारी किया BJP का संकल्प पत्र

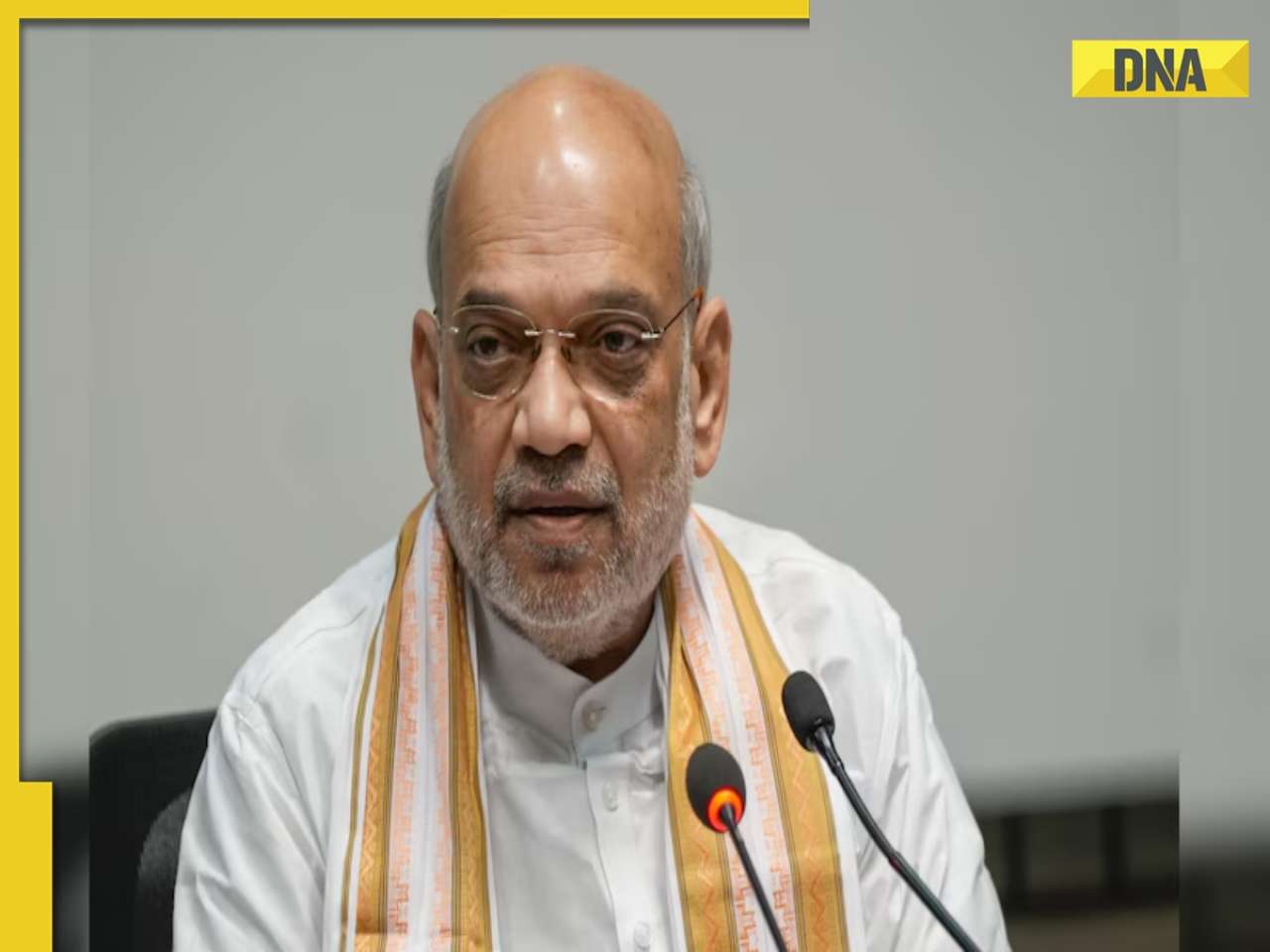

J-K विधानसभा चुनाव: 'आर्टिकल 370 को हम कभी वापस नहीं आने देंगे', अमित शाह ने जारी किया BJP का संकल्प पत्र![submenu-img]() Kanhaiya Lal Murder: कन्हैयालाल हत्याकांड में दूसरे आरोपी जावेद को भी मिली बेल

Kanhaiya Lal Murder: कन्हैयालाल हत्याकांड में दूसरे आरोपी जावेद को भी मिली बेल![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details![submenu-img]() Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design

Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects

UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects![submenu-img]() Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...

Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…

Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…![submenu-img]() Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed

Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed![submenu-img]() 'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project

'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project![submenu-img]() Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure

Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure![submenu-img]() Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested

Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here

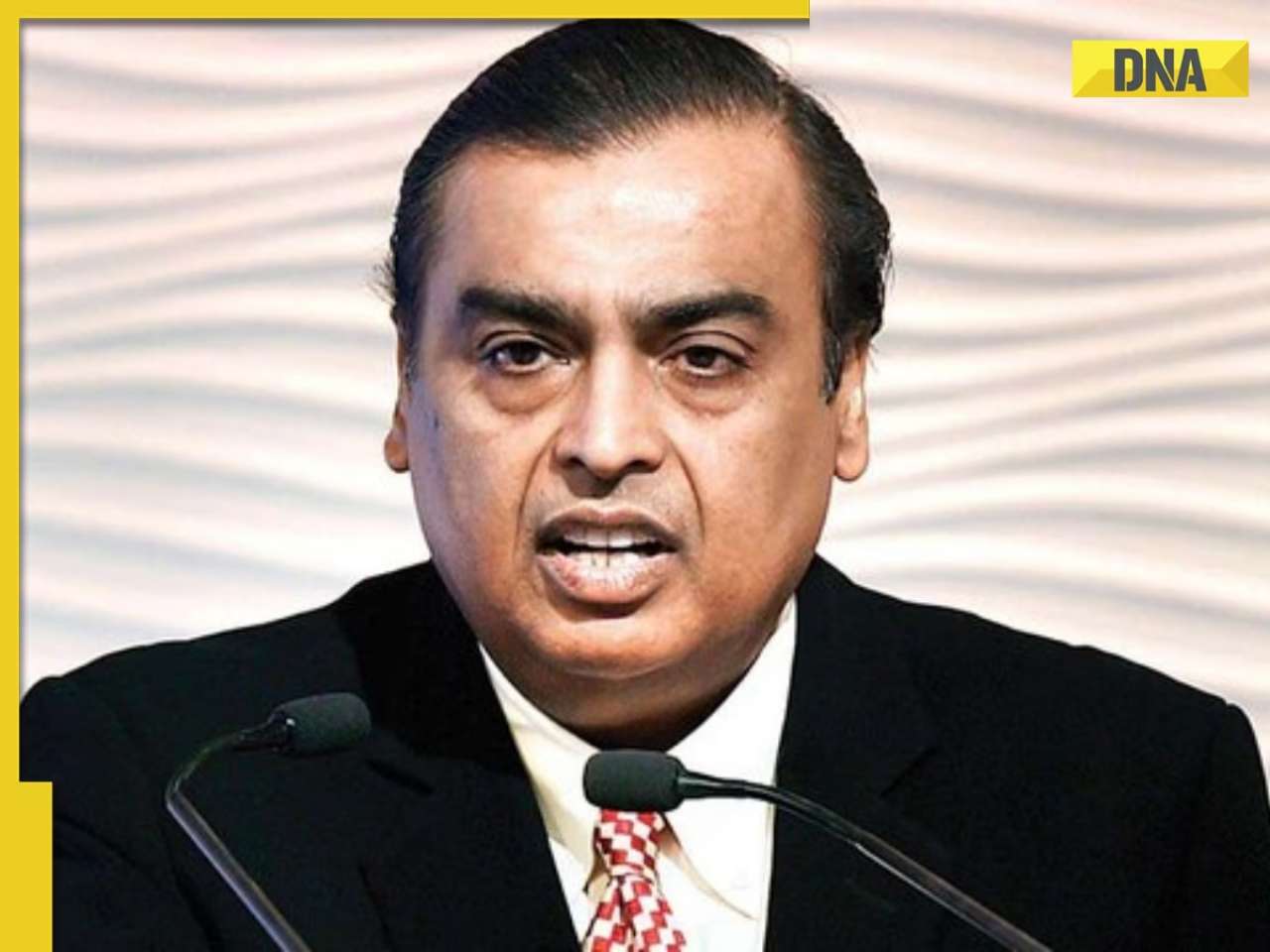

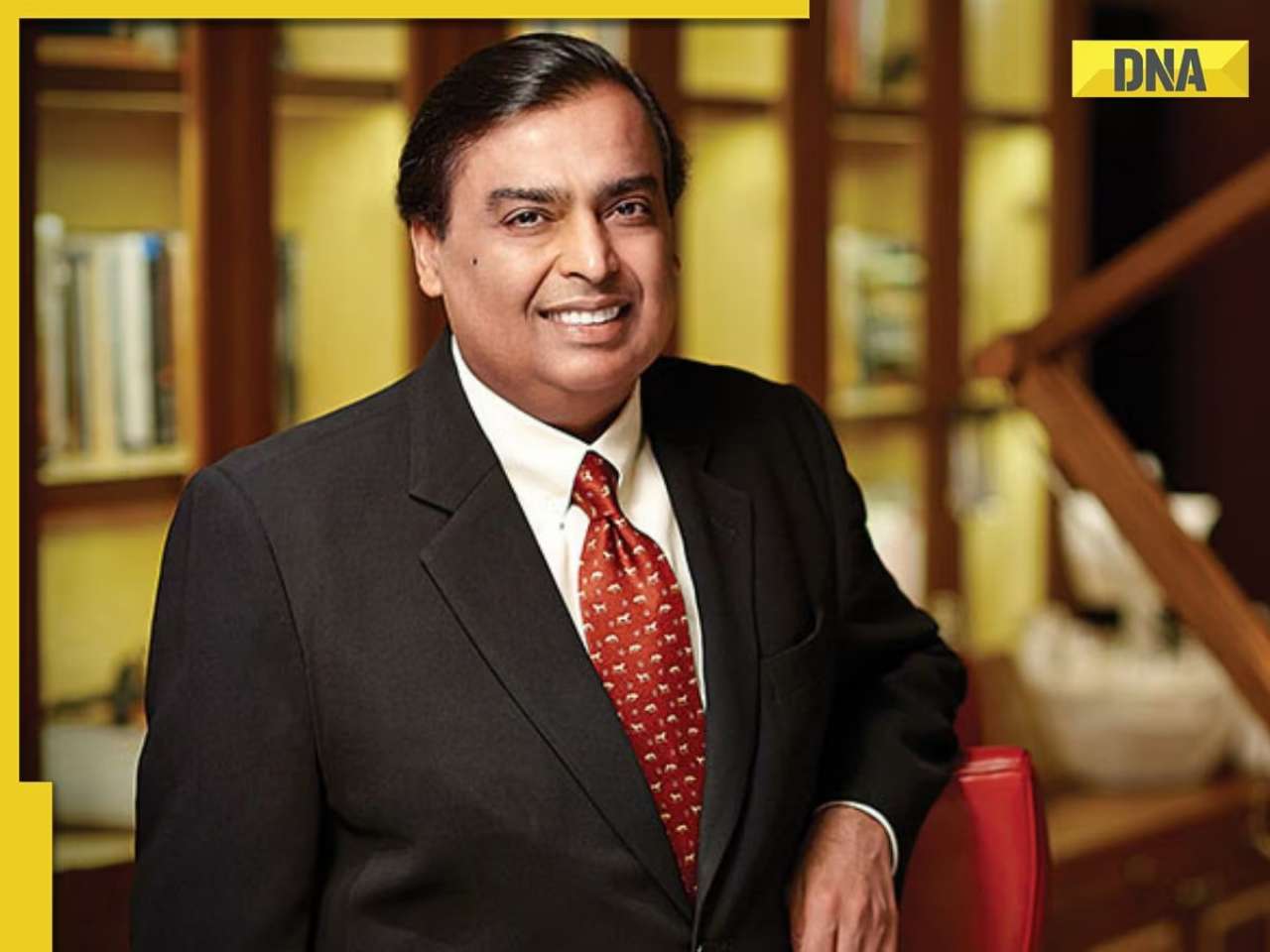

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...

Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...![submenu-img]() NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works

NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...

Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...![submenu-img]() This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection

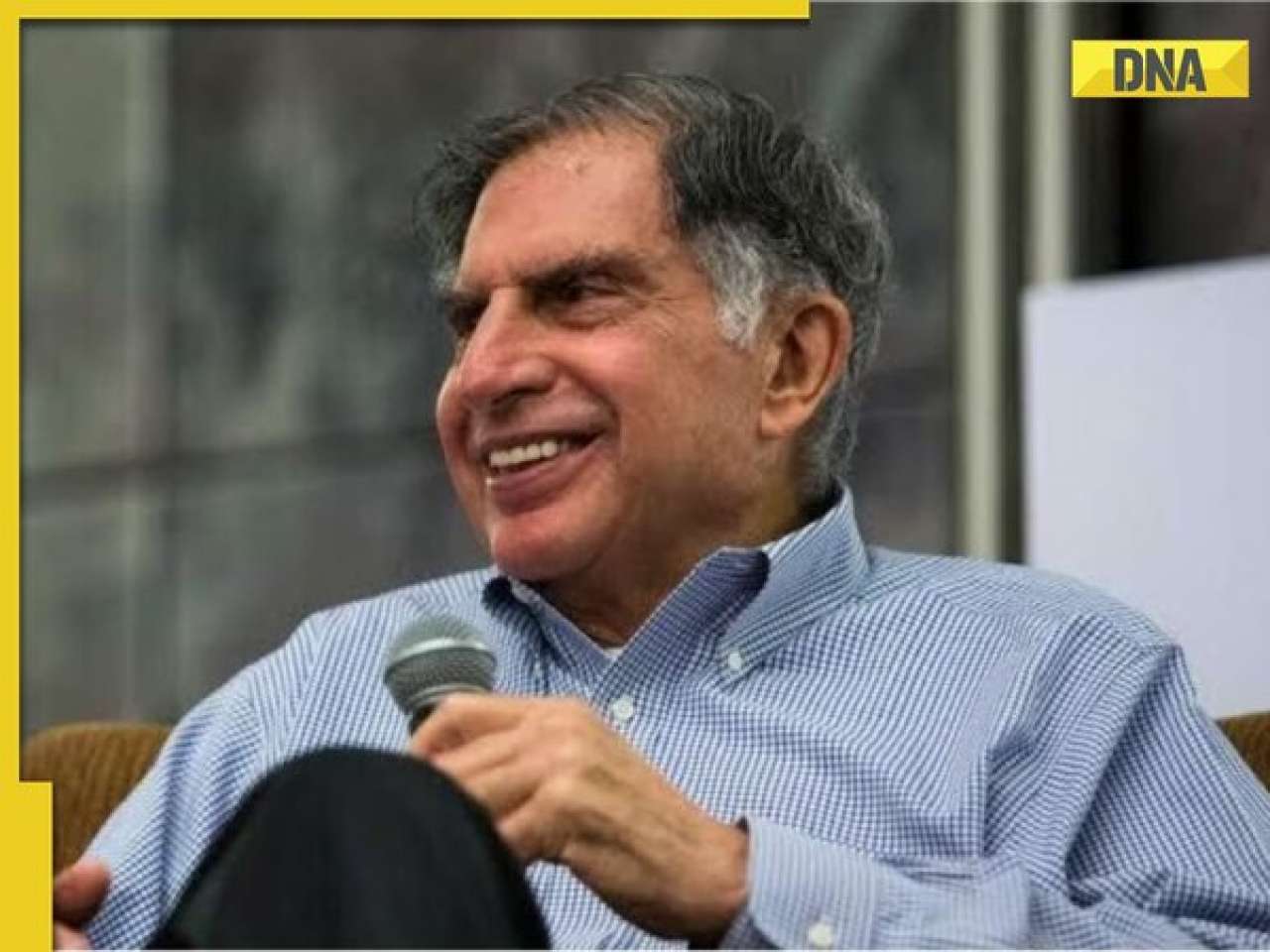

This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection![submenu-img]() Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...

Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...![submenu-img]() From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months

From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...

Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...![submenu-img]() Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival

Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival![submenu-img]() Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body

Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body ![submenu-img]() Active players with most centuries in international cricket

Active players with most centuries in international cricket ![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() 'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP

'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP![submenu-img]() India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...

India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...![submenu-img]() Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)