In his books, bestselling British novelist Sebastian Faulks may seem preoccupied with love, war and France, but it is “that elegant logic in madness” that fascinates him the most, finds DNA, who met him at the Hay Literature Festival in Trivandrum last week.

In his books, bestselling British novelist Sebastian Faulks may seem preoccupied with love, war and France, but it is “that elegant logic in madness” that fascinates him the most, finds DNA, who met him at the Hay Literature Festival in Trivandrum last week.

Almost 10 years ago, Sebastian Faulks sat across a woman for an unusual experiment that involved a mock interview. She gave him a walkman and the author was expected to answer her questions while listening to it.

“So, why is this job important to you?” she asked. As Faulks prepared for a reply, a voice in his ears said, ‘You f***ing loser, so you think you’re fit to go around job-hunting?’

Faulks was flustered. He heard the lady’s voice again. “Who was our prime minister before Tony Blair?” Faulks knew the answer but the voice in his ears said, ‘So, you think you know the answer to that, you rotting f***er?

At this point, Faulks took off the earphones. “You didn’t do too well, did you? Well, at least you know how it is to live with schizophrenia,” commented the lady who suffered from the disorder.

That moment on, Faulks knew he was ready to make a sharp deviation from his choice of subjects in previous novels. The concept of madness gripped the writer who loved writing on love, war, France and women.

Mysteries of the mind

Born in Donnington, a village near Newbury in Berkshire in 1953, Faulks began writing in 1984 (A Trick Of The Light) but rose to fame in 1993 with the love saga, Birdsong. It was in Human Traces (2005) that he got to explore the mysteries of the mind and madness.

Stretched out on a couch in the ‘Author’s Room’ at Kannakakunnu Palace, the venue of this year’s Hay Festival that was held in Trivandrum from November 12-14, Faulks discusses ‘madness’ with a hint of reverence. “When I was 10 years old, my godmother’s son developed schizophrenia at 21. It was like meeting a person whose body was inhabited by a stranger. Over the years, at least four people around me suffered the same fate.”

What strikes Faulks as ludicrous even today is people asking questions like, ‘Is it all in the mind, or is it even real?’ He began researching schizophrenia obsessively, and was surprised to find how psychosis isn’t known to strike other living beings.

“Cows or dogs, for instance, don’t imagine that their thoughts are being broadcast on national TV. It’s only our ‘evolved’ human mind that does, when it is psychotic. We can never understand the human brain fully without studying what goes so wrong with it. It seems madness is the price humans have paid to reach here.”

The schizophrenic woman he spent time with told him how a voice in her head once convinced her to strip on a busy London street.

Another voice that advised her otherwise was nagged by the former. “It was shocking how exceptionally intelligent she was when the medicines were effective.”

Loving women and history

Over years, even Faulks’ critics cannot deny that he writes about women and their love with the ease of, well, a woman who has lived it all. The only time his formula seems to have failed is when he won Literary Review’s 1998 Bad Sex Award for Charlotte Gray.

Otherwise, Faulks’ novels have a way of forging right up to the bestsellers’ shelf at UK’s bookstores.

Faulks’ work is his way of shaking off some bad advice he got in his 20s — to always write what he knew about. He says writing about a past liberates him. He looks down on that you-know-what-I-mean nudge a writer can afford to give readers while writing about the present. “I have never walked into bullets in a war. I love to imagine the taste in my mouth, or the way my hands would hang by my side if I had to do that. Isn’t that the biggest stretch to give your imagination?” he says, putting his hands out. “And to write about how a French woman in the 30s would react to an unusually difficult situation?”

At this point, Faulks turns in his seat and smiles eagerly. He says he found a way to indulge his imagination right from his boarding school days. When his class was first introduced to classics like David Copperfield and Pride And Prejudice, he pretended to stifle yawns like the rest of the boys. But at night, hidden under many blankets, Faulks was exhilarated. Carrying a secret like that made Faulks feel “powerfully anti-authoritarian”, an element he loved in DH Lawrence’s writing. The idea of doing something subversive and “naughty” tickled the teenage Faulks to no end. It still does (he’s the man who penned the James Bond thriller, Devil May Care just for fun and to see if he could finish it in six weeks like Fleming did. He could). “I felt so sorry for James Bond, this lonely, vulnerable guy with soft shoes, a puny gun who has enemies with far better ammunition…” he says, with an earnestness you would almost believe if it weren’t for the mirth that follows.

At 15, Faulks knew he wanted to be a writer without knowing how to write — which explains his stint as a schoolteacher and his first job as a reporter who reviewed books too. Faulks went on to become the first literary editor of The Independent and became a columnist for The Guardian and the Evening Standard.

Back to the present

Faulks says he could no longer ignore writing about the present when he saw his kids surrounded by technology and social networking. Unlike him, his three children exhibit no curiosity about their surroundings in a foreign land because their Game Boys monopolise all their attention. His recent book, A Week In December, is about hedge fund managers, religious fundamentalists, and psychotic reality television contestants competing to win free healthcare.

“A Week In December is my way of coming back to a world where I believe the internet culture has a dehumanising effect and television is sucking out any possibility of having an intellectual life,” he shrugs.

Interestingly, Faulks set out for the book with the intention of writing a “modern Dickensian novel”. You cannot help but smile at him for putting it that way. No matter when and where his books are set Faulks won’t walk away from the past.

![submenu-img]() Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa

Ganesh Chaturthi 2024 shubh muhurat: Check city wise puja timings, visarjan date, and bhog for Ganpati Bappa![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'

Boney Kapoor announces new film, its title has a Mr India connect: 'Probably by December we...'![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...

Meet actress, who worked for 17 hours straight on toxic sets, her mental health was affected, left industry, is now...![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

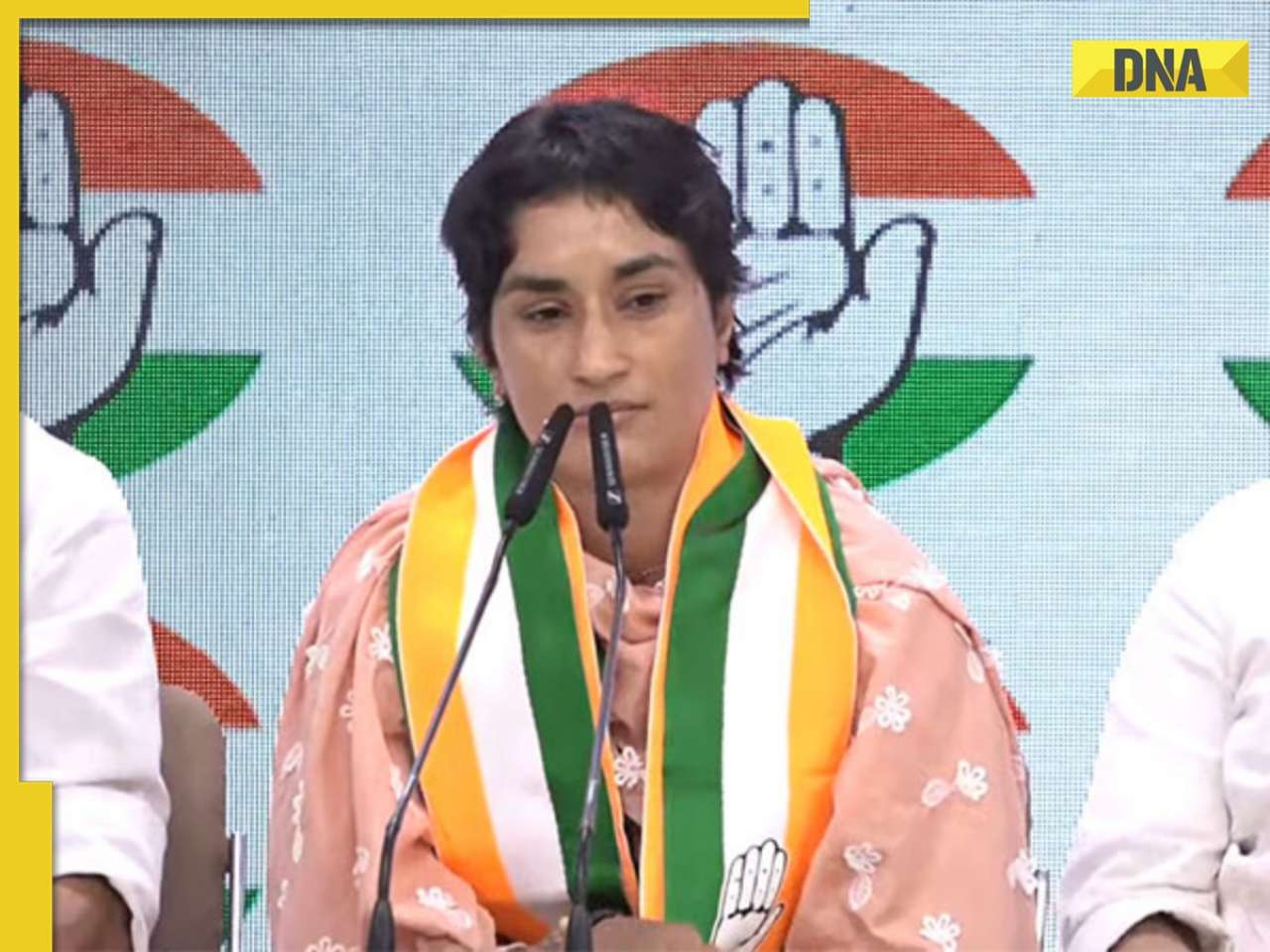

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: हरियाणा में कांग्रेस प्रत्याशियों की पहली लिस्ट जारी, इस सीट से चुनावी मैदान में उतरी विनेश फोगाट![submenu-img]() Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल

Hathras Accident: यूपी के हाथरस में बड़ा सड़क हादसा, 15 लोगों की मौत, कई घायल![submenu-img]() Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट

Weather Alert: महाराष्ट्र-गुजरात में जोरदार बारिश, आंध्र-तेलंगाना में बाढ़, जानें दिल्ली-एनसीआर के लिए क्या है अलर्ट![submenu-img]() J-K विधानसभा चुनाव: 'आर्टिकल 370 को हम कभी वापस नहीं आने देंगे', अमित शाह ने जारी किया BJP का संकल्प पत्र

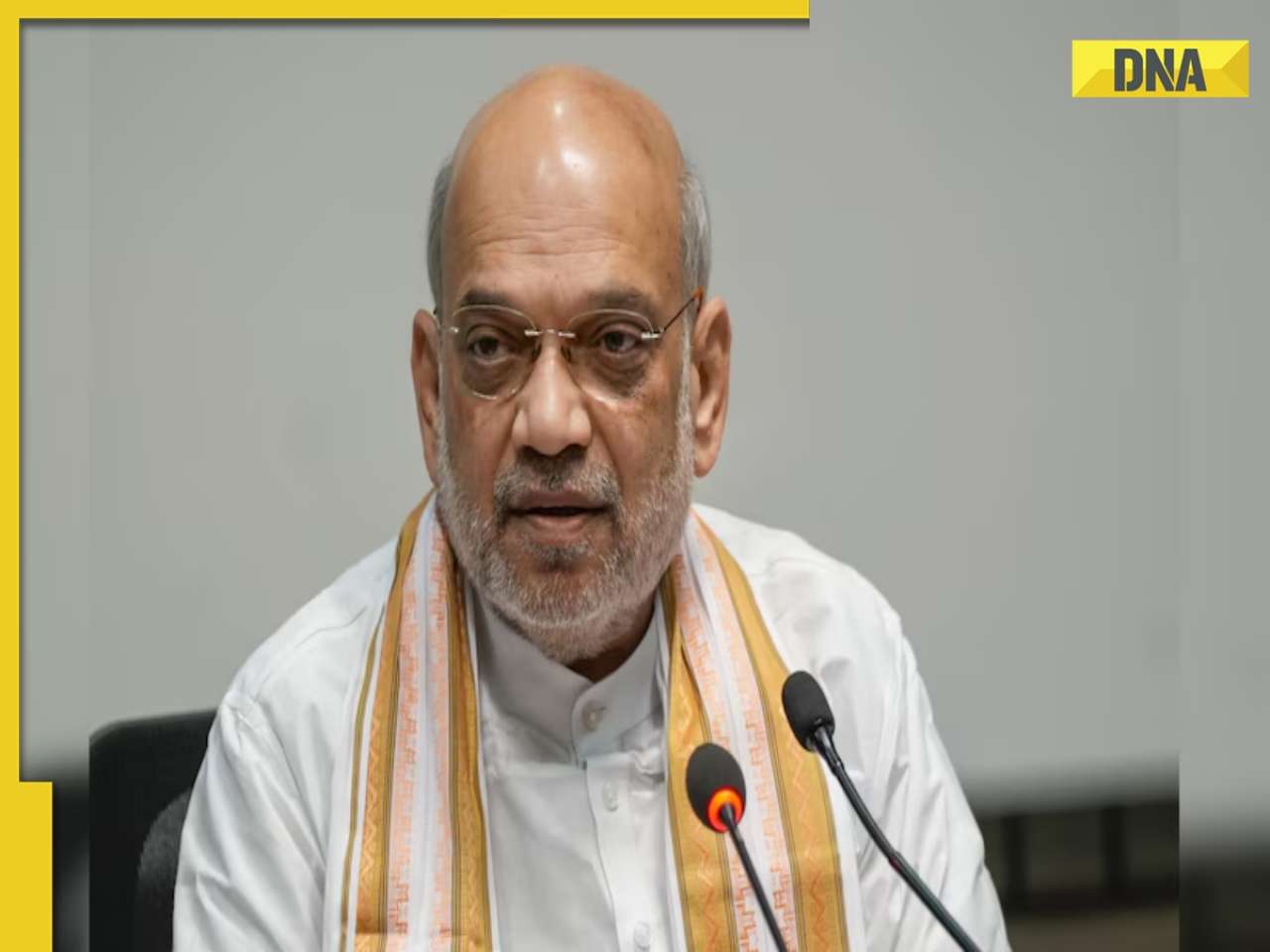

J-K विधानसभा चुनाव: 'आर्टिकल 370 को हम कभी वापस नहीं आने देंगे', अमित शाह ने जारी किया BJP का संकल्प पत्र![submenu-img]() Kanhaiya Lal Murder: कन्हैयालाल हत्याकांड में दूसरे आरोपी जावेद को भी मिली बेल

Kanhaiya Lal Murder: कन्हैयालाल हत्याकांड में दूसरे आरोपी जावेद को भी मिली बेल![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

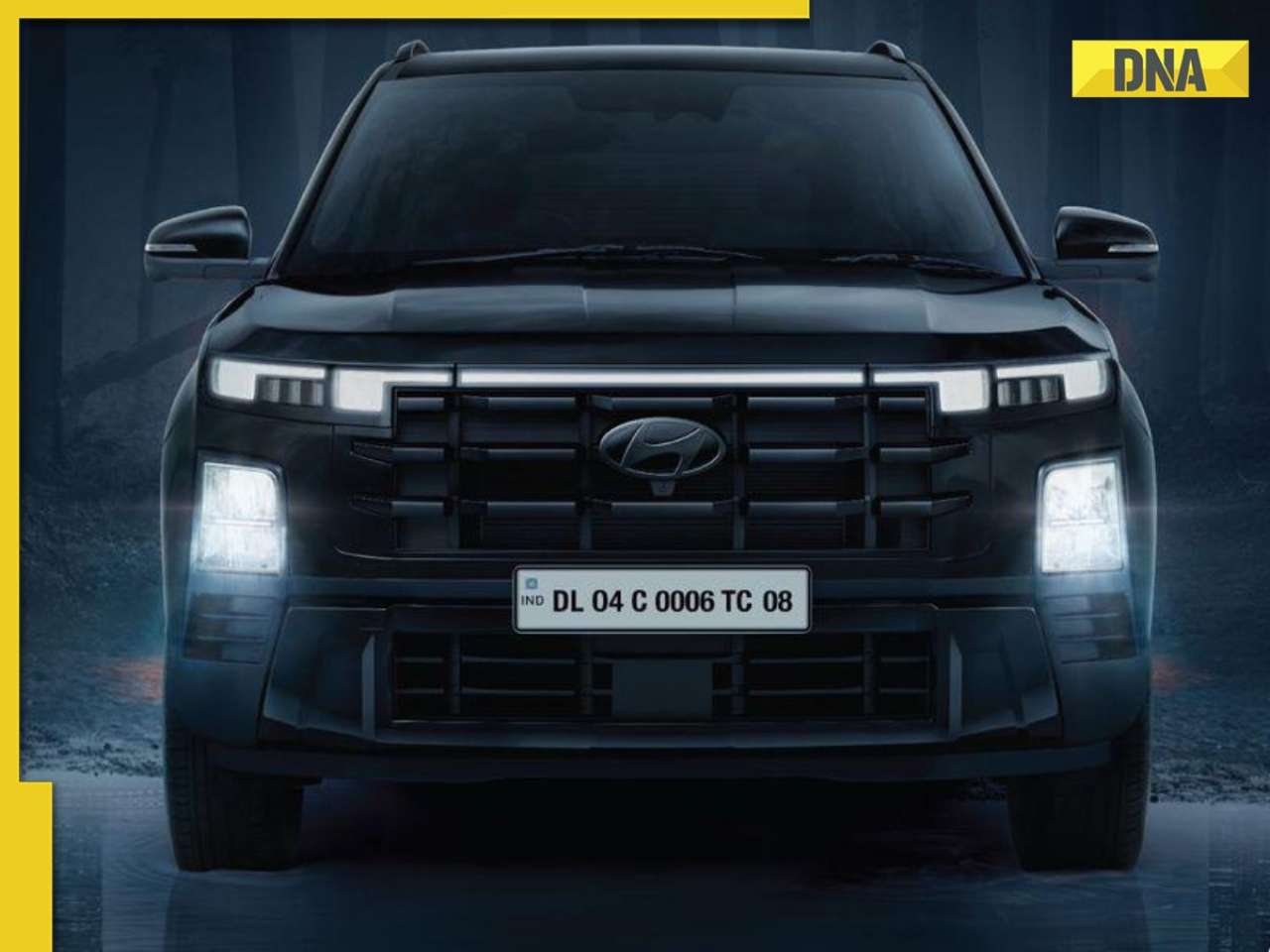

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Maruti Suzuki Swift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Hyundai Alcazar Facelift nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check details![submenu-img]() Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design

Hyundai Creta Knight Edition launched in India: Check price, features, design![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Citroen Basalt nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features

DNA Auto Awards 2024: Tata Curvv nominated for ‘CAR OF THE YEAR’; check price, features![submenu-img]() UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects

UPSC topper IAS Shruti Sharma's marksheet goes viral on social media, check her scores in different subjects![submenu-img]() Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who lost his mother in childhood, worked as milk seller, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...

Meet man who failed 35 exams, cracked UPSC exam twice, first became IPS then quit due to...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...

Meet man, who was forced into child marriage at 11, cracked NEET exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…

Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt without coaching at 22, got AIR 31, she is now posted as…![submenu-img]() Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed

Mumbai: Fire Breaks Out At Times Tower In Mumbai, 9 Fire Units Deployed![submenu-img]() 'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project

'Dharavi Project Is About Restoring Dignity...', Says Gautam Adani | Dharavi Redevelopment Project![submenu-img]() Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure

Kolkata Doctor Case: CBI Visits RG Kar, Seizes Documents On Funds Used During Sandip Ghosh’s Tenure![submenu-img]() Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested

Giriraj Singh Attacked: Union Minister Giriraj Singh Assaulted In Begusarai, Bihar; Accused Arrested![submenu-img]() Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here

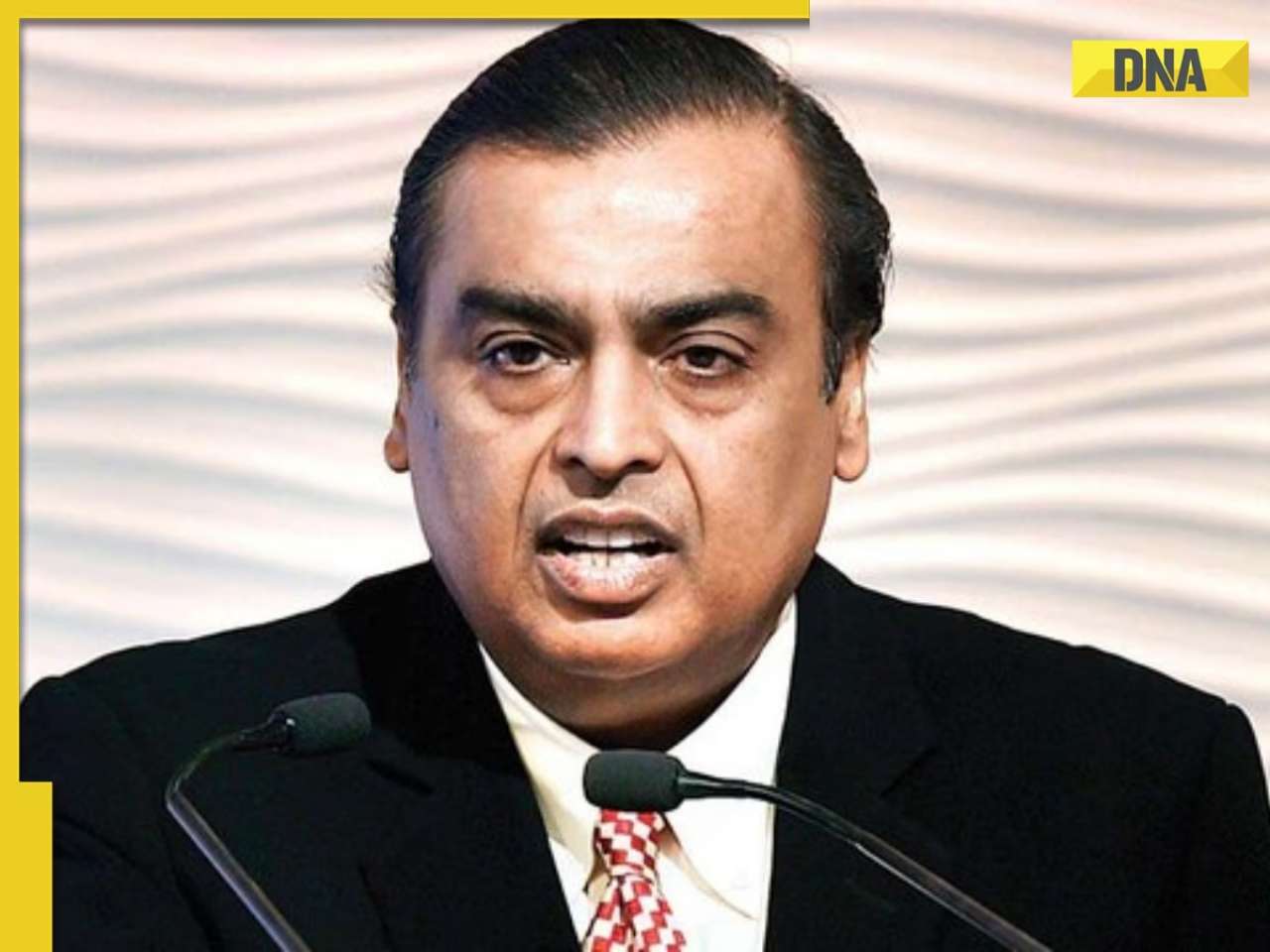

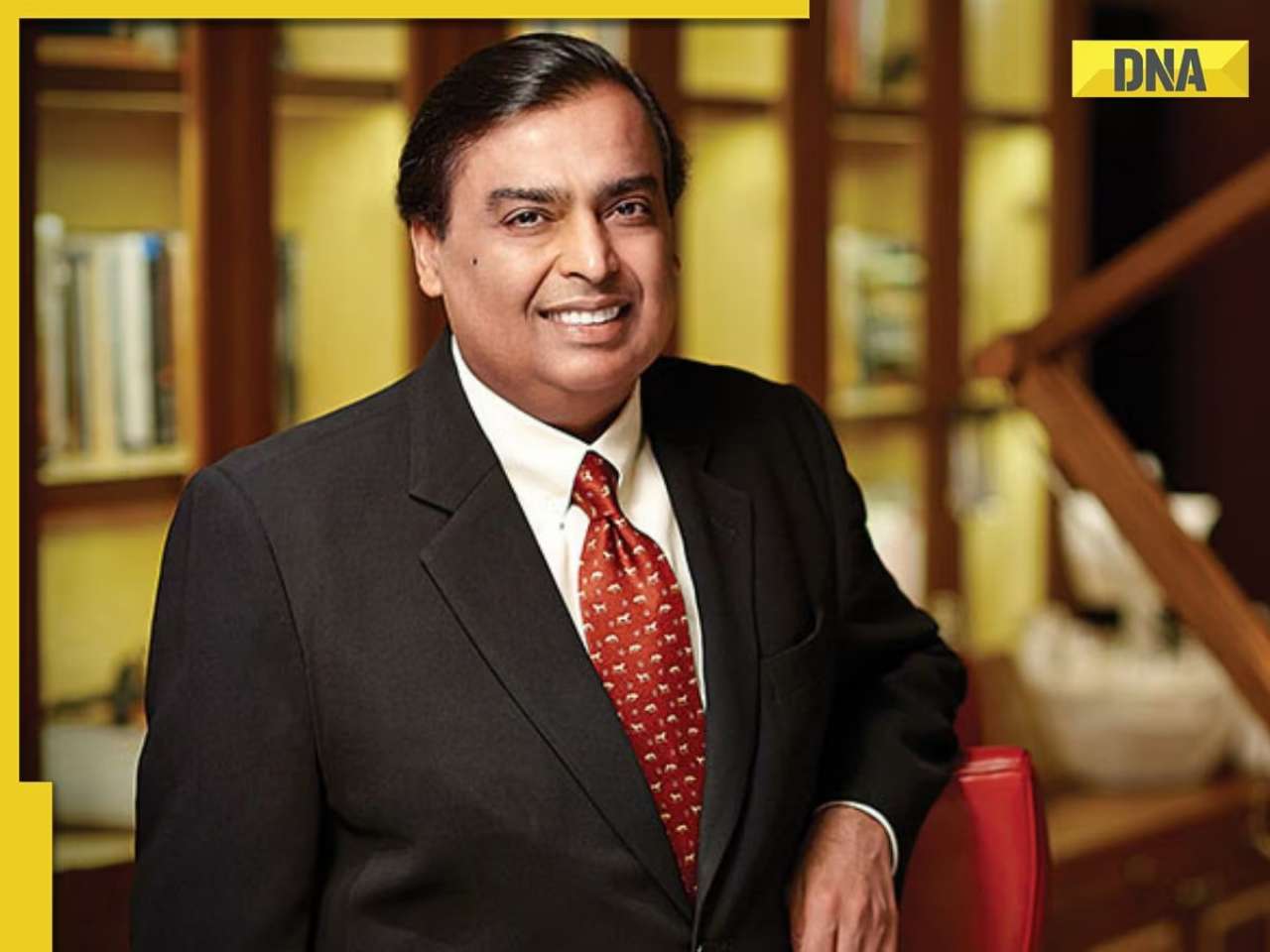

Haryana Assembly Election 2024: Haryana Assembly Election Date Changed, Check Details Here![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...

Mukesh Ambani set to challenge Adani, ITC with his Rs 3900 crore plan for...![submenu-img]() NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works

NPCI launches 'UPI circle', check what it is and how it works![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...

Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Jio to give tough competition to BSNL with this plan, it offers 5G data at just Rs...![submenu-img]() This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection

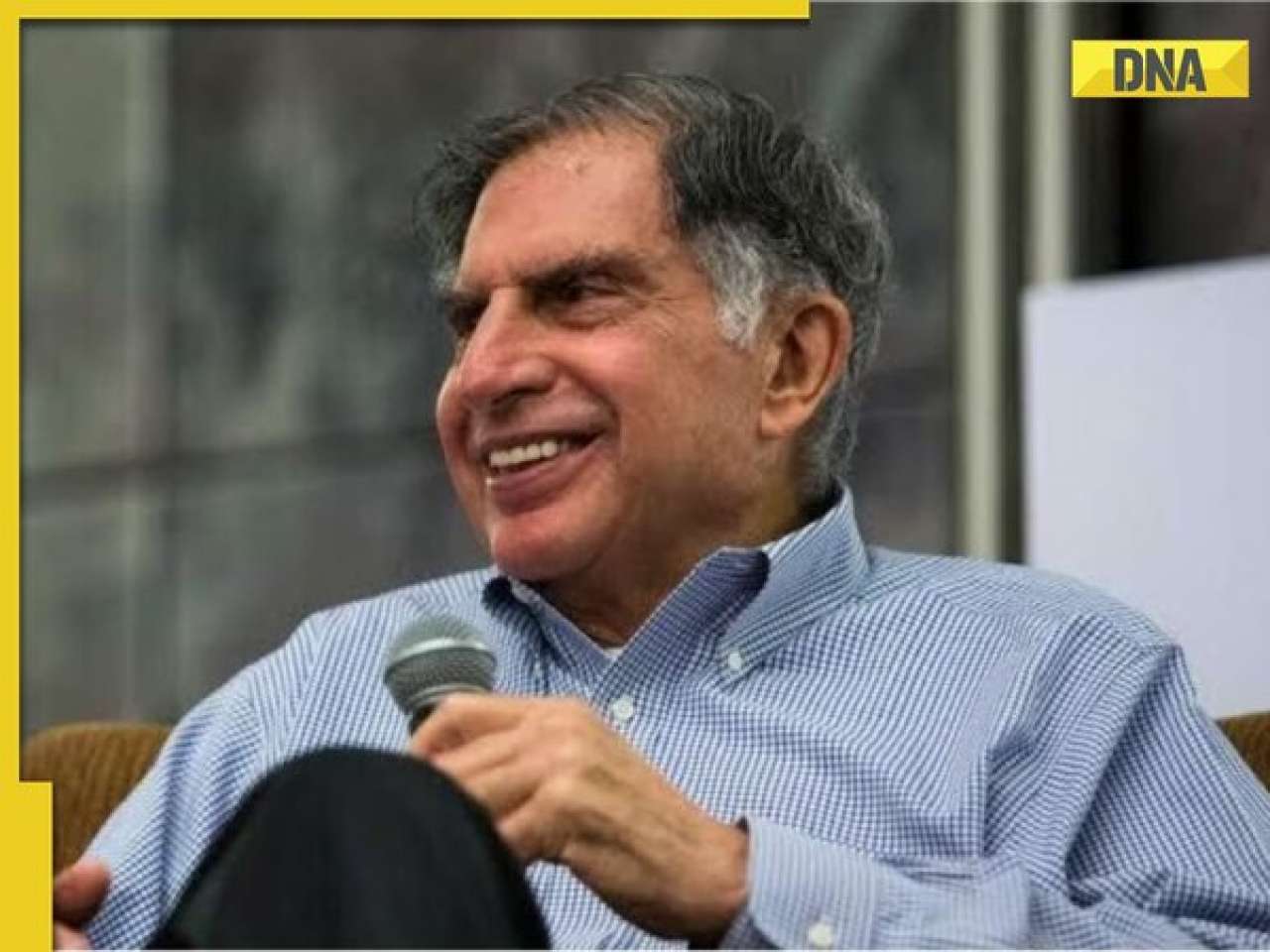

This company repays Rs 20000 crore debt for... and it has a Ratan Tata connection![submenu-img]() Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...

Meet woman, billionaire's daughter, who studied in London, now leads Rs 1124 crore company as...![submenu-img]() From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months

From Cristiano Ronaldo to Virat Kohli: List of highest-paid athletes in last 12 months![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...

Meet actor who worked as waiter, sold tea, namkeen for 14 years, debuted in Bollywood at 42; now his net worth is...![submenu-img]() Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival

Parents-to-be Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh seek blessings at Siddhivinayak with families days before baby's arrival![submenu-img]() Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body

Gout remedies: 7 natural ways to lower uric acid levels in the body ![submenu-img]() Active players with most centuries in international cricket

Active players with most centuries in international cricket ![submenu-img]() 'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'

'Leaders in Delhi never liked me…’ Omar Abdullah alleges poll 'conspiracy'![submenu-img]() Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'

Over 200 Patients celebrate freedom from diabetes in Madhavbaug's nationwide campaign 'Azadi Diabetes Se'![submenu-img]() 'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP

'When we were dragged on roads...': Wrestler Vinesh Phogat slams BJP![submenu-img]() India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...

India emerges as second-largest global 5G smartphone market, overtakes...![submenu-img]() Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

Union Home Minister Amit Shah releases BJP manifesto for J&K assembly elections

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)